The first part of this series, where I talk about the historical context for superhero movies as a genre, is here. The second part, where I talk the superhero movies I think are the best, as well as the superhero movies other people think are the best, is here.

The Auteurs of the Superhero Genre

We’re headed back to Martin Scorsese. In A Personal Journey with Martin Scorsese Through American Movies, Scorsese sees the successes of American movies through the lens of the auteur, and more than that, the lens of a director who must adjust to external pressures in order to make a personal film. The director must “smuggle” his or her ideas into a movie in order to make them palatable as entertainment. Here’s where he underlines Ida Lupino, Joseph H. Lewis, and Jacques Tourneur. Or, the director may be an “iconoclast,” someone who damns the torpedoes and does everything possible to make the picture in his or her own way. With John Cassavetes, that might mean no budget. With Josef von Sternberg, that might mean a very short shelf life. With Stanley Kubrick, that might mean running away to London and throttling his creative output into only a relative few movies. Scorsese understands the power of a producer, certainly, citing David O. Selznick and Val Lewton among others who could rule a set with an iron hand. But for all the influence of Lewton, Scorsese is still more interested in Jacques Tourneur. For as much as Selznick dominated Duel in the Sun, the story for Scorsese is in the greatness of King Vidor.

I have my own misgivings about auteur theory, which is fashionable for people to say now, just as ascribing to it was once fashionable for people like me. But this is nevertheless a useful lens. Where Andrew Sarris saw Hollywood filmmaking through the 1960s as a place where the auteur might smuggle or break icons under the noses of the entertainment apparatus, we ought to do the same for the even more rigorous confines of superhero movies. David O. Selznick was answerable primarily to himself. Kevin Feige is answerable to the Mouse, and to the Mouse’s stockholders, and for as profitable as his movies have been, Feige is no Selznick. Neither are Bruce Timm nor Sam Register. Yet the superhero movies have leeway. Something is still left to the director in execution, though, as Lucrecia Martel can attest, some of the action sequences can only be done in the house style.

What follows is a catalog of directors of the superhero genre, something like what Andrew Sarris did for American cinema in its sound era up through the 1960s. Where I’m going to differ from Sarris is that I’m not going to be able to tell you that there’s a Alfred Hitchcock in here, nor an Ernst Lubitsch, nor any of his “pantheon directors.” If there were such people to study, then by gum we would know it by now. There are exceptional figures thus far, and there are some who are as important to the superhero genre as John Ford was important to the western, or Vincente Minnelli was important to the musical. Again, to be abundantly clear, their importance does not imply greatness as craftspeople. I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe.

The auteurs of the superhero genre come in one of four different flavors: Stampers, Brutes, Iconographers, and Jesters.

The Stamper may have some moments of personality in their films, but that personal vision is subducted beneath some larger goal which the film is in service of. This might be a corporate goal, in which the film is part of the brand first. This might be a focus on a house style, especially in animation. The Stamper may be closely associated with a particular superhero, taking control of a number of projects on the same character. The Stamper may also be content with taking cues from a preexisting text of the same name, adapting a limited series or a graphic novel with special care, sometimes even transposing pages or sequences from the comics into the film. The Stamper rarely asks why a superhero exists, even within the context of an origin story. The most important of the Stampers is Sam Liu.

The Brute is primarily concerned with the superhero as a violent figure. The justification for superheroes might be questioned, but the violence with which the superhero discharges his or her duty is unmistakable. Where other superhero auteurs will try to create metonymic individuals who are saved by the heroes, standing in for the many others we are meant to assume they have saved, the Brute is comfortable with the idea that there will be casualties. The Brute pushes the limits of what might be acceptable for other types of directors in terms of the types, representations, or gazes of violence, e.g. violence against children, superheroes killing their foes, blood and guts. In some ways, the Brute works with realism, insofar as that’s possible, more than others. The most important of the Brutes is Jay Oliva.

The Iconographer typically incorporates elements of a personal style into their film, although it is not unusual to see some of the same concessions to a house style that a Stamper might make. (The Iconographer often has a name brand quality that the Stamper might not.) The Iconographer takes the presence of a superhero to be an obvious good. Where a Stamper simply accepts the presence of a superhero, an Iconographer will make a point of arguing why the superhero is justified, necessary, or laudable. The Iconographer will emphasize “real-world” themes and ideas, referring back to contemporary political ideologies. These directors are more likely than others, with the possible exception of Stampers, to pit the superhero against a supervillain who simply could not be stopped by bureaucracy, constabulary, or armed forces. The most important of the Iconographers is Zack Snyder.

The Jester wants to remind you that the superhero originated because s/he is an entertaining figure. Where humor is often part of the superhero genre, the Jester goes out of their way in order to make jokes the center of the first two-thirds of the film. The Jester prefers self-referential humor and irony. The Jester may occasionally question the need for a superhero, or show concern for the methods by which a superhero attains a state of peace and order, but the Jester is in the service of a monarch. The Jester may have enough authority to poke fun at the genre, or at the individual superheroes in a film, but chooses to accept the presence of superheroes with almost as much approval as the Stamper. The Jester must choose different stakes than other superhero auteurs do, because in effacing the superhero in the first two-thirds of the film, the stakes seem less important. Often the real solution is in maintaining and mending “found family.” The most important of the Jesters is James Gunn.

I lied about there only being four kinds. There’s a fifth kind which we’ll breeze through at the end: people who have only directed one superhero movie so far. You can tell which ones they are because they’ve only directed one superhero movie so far.

I’ve ordered the directors within each group in terms of meaningfulness to the superhero genre at large.

Stampers

Sam Liu

Superman/Batman: Public Enemies (2009), Planet Hulk (2010), Justice League: Crisis on Two Earths (2010, co-directed), All-Star Superman (2011), Thor: Tales of Asgard (2011, co-directed), Batman: Year One (2011, co-directed), Justice League: Gods and Monsters (2015), Justice League vs. Teen Titans (2016), Batman: The Killing Joke (2016), Batman and Harley Quinn (2017), Batman: Gotham by Gaslight (2018), The Death of Superman (2018), Reign of the Supermen (2019), Justice League vs. the Fatal Five (2019), Wonder Woman: Bloodlines (2019), Superman: Red Son (2020), Batman: Soul of the Dragon (2021), Batman: The Doom That Came to Gotham (2023)

Sam Liu has directed or co-directed eighteen superhero features, which is more than any other director in the sample that I’m working from. His work is primarily in one-shots, many of them based on limited runs and graphic novels (All-Star Superman, The Killing Joke, Red Son, etc.), though Reign of the Supermen builds directly on Death of Superman, and his foray with the Teen Titans starts a continuity which would be revisited in Teen Titans: The Judas Contract. Much of Liu’s work is speculative in nature. Aside from All-Star Superman, which would pretty firmly close off Superman if it were to be taken within a timeline, other films are plainly in a different space than the regular timelines we see in the DCAMU. Gotham by Gaslight, which takes place in a Victorian Gotham, and The Doom That Came to Gotham, in which Etrigan teams up with a pre-World War II Bruce Wayne to defeat Ra’s al Ghul, who is trying to bring a Lovecraftian creature into the world. My personal favorite of the bunch is Soul of the Dragon, which riffs on the ’70s kung fu movie. Only a small handful of Liu’s films are of the origin story variety. Batman: Year One, a co-directed movie, stands out in that way, and so does Wonder Woman: Bloodlines, which witnesses Diana’s expulsion from Themyscira and her accession to the role of Wonder Woman in man’s world.

Liu’s three best solo films are Justice League: Gods and Monsters, Justice League vs. Teen Titans, and Batman and Harley Quinn. (Justice League: Crisis on Two Earths has been covered in some detail previously, and was also co-directed by Lauren Montgomery.) These three are, in terms of content, very different from one another.

Gods and Monsters takes place in one of those alternate realities, one in which Superman (fathered by Zod rather than Jor-El), Batman, and Wonder Woman are Hernan Guerra, Kirk Langstrom, and Bekka. The three of them coexist uneasily with the world’s governments. Their powers clearly place them above the law, and world leaders, such as Amanda Waller, can do little more than nag them to submit to federal inquiries. This is one of those grim DCAMU stories with a high body count, though what makes this one stand out is not the stench of its violence but its targets. A number of characters with recognizable names go down in this one, either in a Red Wedding-style flashback sequence starring Bekka or, more often, in sequences where many scientists are killed by assassin robots.

Justice League vs. Teen Titans is a pretty straightforward DCAMU outing, lightened a little more than usual by the presence of the Teen Titans. There’s a long sequence where Damian Wayne beats Gar in a Dance Dance Revolution competition, which I like pretty well. After all, why shouldn’t a nimble trained assassin be able to pick up the rudiments of DDR, thus proving that he can learn to fit in with the other kids? The film focuses on the Titans more than the Justice League, working on its outcasts (Damian and Raven), and in the end, the only one who can defeat the demon Trigon is his daughter.

Batman and Harley Quinn is singular among the animated DC films, a zany adventure of kook and kink. The star is not Batman (who smells a fart and says it smells like “discipline”) or Nightwing (who is tied to a bed before, we are given to understand, he has the best sex of his life). It’s Harley Quinn, freed from the supporting role we so often see her in next to the Joker, and freed as well from her position in the Suicide Squad. Harley is interpreted not as manic but as liberated, and what she does in partnership with Batman and Nightwing is not done to destroy crime but to help a friend. Poison Ivy has teamed up with the Floronic Man to make a point about climate change, but in the end, she can still be swayed by Harley making a sad face at her. It’s not Spider-Man 2, but it’s a heck of a lot closer to Spider-Man 2 than anything else I’ve seen in a DC movie.

Liu’s facility with these different types of stories—I haven’t even talked about his work with Superman, probably the character I’d associate with Liu first—shows that Stampers are not depersonalized directors. Their preferences and concerns will shine through over time, and for Liu, those preferences and concerns are clearer. What makes Liu the prime Stamper is his unquestioning view of the superhero. The position of the superhero is almost always justified in Liu, and concerns about the primacy of the superhero turn to carping. This is what’s being stamped in. Justice League vs. Teen Titans looks at the world and suggests that what it needs is a developmental league for superheroes. Damian is perhaps the most unpopular character in these animated DC movies, and he’s definitely drawn up in such a way that it’s hard to like him. He’s snotty, arrogant in the extreme, and because no one (Batman, Starfire…Alfred…) allows him to kill people once he’s been liberated from the League of Assassins, we don’t even get any proof that he deserves the arrogance we have to face. He takes poorly to being sent to the Teen Titans after a selfish blooper gets him kicked off Justice League duty, understanding it correctly as a demotion. The jokes about boarding school that characters make through multiple Damian movies show up here as well, and the Titans are the closest thing to boarding school that Batman can find for his son.

(Personally, I like Damian, and I like Stuart Allan’s vocal interpretation of the character. After encountering him for the first time in Son of Batman, I had the warm recollection of watching Kitchen Nightmares. In that case, Batman is Gordon Ramsay, and Damian is the petulant restaurateur who refuses to take advice from a Michelin-starred superhero. It’s a comic relationship, amplified by how little Damian looks next to Bruce, but then again, few are the viewers who come to Batman movies seeking humor.)

Justice League vs. Teen Titans sees the need for superheroes in a few ways. The foremost reason for superheroes is that only they have a chance of defeating the enormous threats that face helpless citizens. Raven is the only one who can defeat Trigon, for example. Damian, armed with the kryptonite that Batman keeps handy, is the only one who can defeat a possessed Superman. (See also, from Liu’s oeuvre: only a transfigured Batman can defeat a Lovecraftian monster, only Superman can defeat Doomsday, only Wonder Woman can defeat Medusa…such examples exist all across the types of superhero auteurs.) Superheroes also can defeat a different set of villain, one who does not summon cosmic power but who would strain the resources of a local police force or SWAT teams. In the beginning of the film, the Justice League fights the Legion of Doom; Weather Wizard and Toymaster, battled by the Flash and Cyborg, respectively, represent this kind of adversary.

Perhaps most importantly, at least in Liu’s work, superheroes exist because of their consciences. Conscience is what moves the superhero to take action, and guided by that conscience, a superhero can never go too far wrong. Jaime (Blue Beetle) and Gar (Beast Boy) have abilities which they did not choose for themselves. Yet they are training as minor league superheroes because their consciences dictate that they ought to do heroic deeds for the benefit of others. Most superheroes come to this conclusion so naturally that it barely seems up for debate. In Justice League vs. Teen Titans, only Damian and Raven seem to think hard about their position as heroes, and those two are only forced to think about it because they are still children struggling with their obviously traumatic upbringings. It’s what allows them to act as the credible focuses of the film. Jaime and Gar and Kori have made peace with their situations, made peace with them before the beginning of the film and remain at peace after its conclusion. Damian has to change because he realizes that the goals that he’s set for himself are inflected with the wickedness of Ra’s al Ghul, and thus those goals are not befitting of a heroic person. Raven has to change because she realizes that safety comes in fighting for those you love, not in hiding them. (That the answer to “What brings safety?” is “Literal fighting” is one of the simplest points in the superhero catechism.) All of these are pretty straightforward raisons d’être for superheroes, and Liu gives us those reasons straightforwardly in Justice League vs. Teen Titans.

In other Liu films, the question of the superhero’s conscience is approached more unusually. In Justice League vs. the Fatal Five, the protagonist is a popular DC character who goes mostly unnoticed in other DC movies. That’s Jessica Cruz, one of the Green Lanterns, and in The Fatal Five, she is extremely unwilling to use the powers she is imbued with. The superhero who does not want to take up his or her place in the line of duty is a fairly common story. In First Class, Charles and Erik walk up to Logan, intent on adding him to their lineup of X-Men. They introduce themselves. Logan replies, “Go fuck yourself.” The story is handled with more gravitas elsewhere. Rogue’s attempt to run from her powers in X-Men stands out, given that she might reasonably view them as an uncontrollable curse. Green Lantern: Beware My Power even does something similar, in which John Stewart, ravaged with PTSD, runs away from the ring for the majority of the movie.

In The Fatal Five, Jessica seeks to run away from her powers because it’s not clear to her that what’s bestowed on her is, in fact, meaningful. She was unable to prevent the murder of some friends, and was nearly murdered herself. Given that fear is the enemy of all Green Lanterns, the fears that she carries about herself, and the ambivalence that engenders in relation to her powers, Jessica is temporarily weakened. Yet this is not a Dark Knight Rises situation where she is intent on regaining her position as a superhero. Jessica is out on the idea entirely, and it requires not just the presence of supervillains to animate her again, but the success of those villains as they brutally defeat other Green Lanterns. It is not simply that Jessica is reluctant, which is strange compared to so many other films in which the superhero leaps in immediately. It’s that the history of the 31st Century, where a mentally ill Star Boy comes from and which he references often, depends on Jessica Cruz outshining Superman and Wonder Woman and all of the other heroes of the Justice League in order to defeat the Fatal Five. Because of Star Boy, we know for certain that all of Jessica’s refusals will be outweighed by a single decision to do the brave thing and defeat these 31st Century villains. Even when it seems that a superhero must struggle with her conscience in order to attain her status again, history itself conspires against that interpretation. She was always going to act in her capacity as a Green Lantern. In that way, it’s as if her conscience never wavered at all.

The other example that leaps to mind is All-Star Superman, an adaptation of a twelve-issue Grant Morrison run of the same name. In it, Superman, exposed too closely to the yellow sun, has gone beyond the previous peak of his powers and in so doing is wearing out. He will die. How Superman chooses to spend the last weeks of his life puts his values into stark relief. It turns out that Superman spends most of that time with the two people nearest to him. First, he goes to Lois Lane, coming up with a serum that makes her as powerful and gifted as Superman for twenty-four hours. This interlude is marred by a competition with some time travelers, but on the whole, it’s sweet. A dying Superman intends to spend his last days with the one he loves. Then, even when some vexatious troublemakers barge in on the Man of Steel, the rest of the movie really circles the relationship between Superman and Lex Luthor.

The superhero, after all, is defined not by his relationships with mortals, not by the relationships that s/he can have with other people which are like the relationships we can have with other people. The superhero is defined by the relationships s/he has with people we cannot fathom, and so it is that Clark Kent gets an exclusive interview with Lex while he waits to be sent to the chair. The way that the two circle one another is at the heart of this movie. Luthor, loquacious to the point of rambling as he talks about himself, his plan to eliminate Superman. Superman, coolly saving Luthor’s life by pretending to be klutzy ol’ Clark, foiling Luthor’s attempts to manufacture enough serum to make a SuperLex. Other distractions pop into All-Star Superman; it’s no surprise that this story was adapted, in a literal sense, from twelve different things. What’s interesting about All-Star Superman is that the decision to highlight Luthor as the mirror of Superman, to find the conscientious hero above all else, pervades the choices in adaptation.

There’s a well-remembered piece of the Morrison book where Superman prevents a young girl from death by suicide. That doesn’t make it into All-Star Superman, and while Liu has talked about that cut as a victim of runtime, it’s worth considering what does make it into the film. Atlas, Samson, the Sphinx, the shrunken city of Kandor, the intrusion of Bar-El and Lilo, the massively powerful Solaris, and multiple points of entry for Lex Luthor. All of those require Superman. They require the conscience of a person who has colossal abilities. But you, gentle reader, might be able to prevent suicide. Normal people do it every day, and not one of them has the proportional strength of a person born on a planet under a red sun. The superhero, in Liu, leaves the prosaic to us. In so doing, s/he tends to leave tenderness to us as well. Conscience dictates the doing of great deeds, not small.

Sam Raimi

Darkman (1990), Spider-Man (2002), Spider-Man 2 (2004), Spider-Man 3 (2007), Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

In Raimi’s films, superheroes do exist because those gifted people are placed in situations where they are too needful of their power to let go of the gift. Superhero work is personal for Raimi in a way that it’s rarely personal for directors working on Marvel or DC IP. (Nothing could be less personal than the stuff that the various Doctor Stranges, or is it just one, who really cares, are doing in Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness. Thus a real turd of a motion picture.) Peter Parker doesn’t strictly need to be Spider-Man until he locks himself into the role when Uncle Ben is murdered, but once he begins to be Spider-Man, it isn’t something he can ever put down again. He tries to put it down in both sequels, looks for ways to give it up so he can make ends meet or so he can express the anger he feels, but one simply does not give up being Spider-Man. People close to Peter are constantly threatened, and thus Spider-Man must always answer the call.

The heart of Raimi’s superhero ethos is in Darkman, who barely fits the description of a superhero at all. When Peyton Westlake looks in the mirror when the lights are low, he sees Jack Griffin, the Invisible Man. Westlake was in the wrong place at the wrong time, one of those scientists on the edge of a breakthrough who gets left for dead, whose body isn’t even identified as his own when he’s found clinging to life, and who resurfaces as a man with a terrible, yet solvable, problem. He has been burned into oblivion and he has no chance of returning to his former life, with girlfriend and steady job in tow. But his research and his programs are still intact enough that he has a chance to do something magnificent. No one is closer to inventing a synthetic skin than Westlake. All he has to do is work out the final kinks in its design (too much direct sunlight makes it fall apart), and he might be able to live again.

Westlake’s crime-fighting efforts lack the universality of your average superhero. There is no focus on crime or injustice outside of the injustice that has been done to him, which puts Westlake in conversation with Frank Castle and not that many other people. Death is not too high a price to pay for malefactors, although only very special individuals at very dramatic intervals of the movie receive dispatches at Westlake’s own hands. There is no expectation that after Westlake has gone through Durant and Strack he will move on to stymie the other white-collar criminals. Westlake is a man with just one job, and just one purpose, and it is really tough to put those kind of single-issue voters into the superhero electorate. The more violence he deals out, the more he begins to enjoy what he’s doing. The rhythms from The Invisible Man are tapped into, as the foul humor of a dangerous man yields to the mania of a murderous one. Our sympathies remain with Westlake throughout the movie, not least when he’s trying to reconnect with his girlfriend wearing his old face through as much sunlight as the synthetic skin can stand. However, this is the pity we grant to a vigilante, not the respect given a sigil, and so the line between superhero and Universal movie monster grows ever thinner throughout the movie. To avenge himself and his future, he must lean ever more into his superpower of creating these exact masks.

Raimi’s Darkman may not ask that many questions about what Westlake’s legal purview ought to be, or if there ought to be other people like him in the world. What interests Raimi is whether Peyton Westlake can coexist at the same time as Darkman (a name which is not spoken until the closing moments of the film). To borrow from Paramount’s library instead of Universal’s, Westlake has reversed the polarity of the problem of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Is Jekyll or Hyde the true owner of the body? Is Westlake or Darkman the true owner of his? The one with death at his fingertips in Darkman is the one who looks like Jekyll, the handsome scientist; the one scrambling for a solution to his problems is the deformed Hyde. Where does the man end and the costume begin? It is one of the most frequent questions of superhero movies, whether it is the legal questions raised in Civil War or the little nod that Bruce, sitting with Selina, gives to Alfred in The Dark Knight Rises. To Raimi’s credit, no one has ever been quite as interested in the mask/man point of separation as he is in Darkman, for nowhere else can we find a superhero whose plans are so intensely personal. Darkman is not a job, a secret identity, or a symbol. It is the final destination of Peyton Westlake, who even before he was Darkman was possessed of the same basic motivations and tools. Once joined, can the two ever really be separated? Looking at the final shot of the movie (where Bruce Campbell, as always, pops up), the answer appears to be a pretty firm “no.”

In his Spider-Man entries, Raimi sees the the superhero and the man inside the mask as functionally inseparable. One can, and does, go on about the sequence where Peter Parker pops up in front of Doc Ock and convinces him to go down a better man than the tentacles have made him. But it’s also in Spider-Man, where the famous upside-down kiss happens. Mary Jane rolls the mask up so that Peter’s lips are visible but so Peter’s face is invisible to her. It is both Peter and Spider-Man who are on the receiving end of her affections, one of them equivalent to the other, and the kiss is therefore doubly sexy.

Jon Watts

Spider-Man: Homecoming (2017), Spider-Man: Far From Home (2019), Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

If Liu represents some of the amiable possibilities of the Stamper, in which ideological consistency expresses itself through many variations of story, Watts represents the pernicious in this directorial framework. No superhero director has more fundamentally misunderstood the character s/he works with than Watts.

The most effective treatments of Spider-Man on film engage with a genuinely complicated individual. First, Peter Parker is young. (Miles Morales is even more emphatically a child, though Watts has never worked with Miles, and so we’ll stick to Peter here.) As Spider-Man, he is the most gifted and powerful young person going, but he is still stuck with the child’s limitations. Even when the character ages, he never seems to age too far. Aunt May is always a maternal figure who he has daily responsibilities to. His love life is the twisty and turbulent love life of a young person, not the mature or settled life of a married man. The villains he fights are older, more seasoned. Sam Raimi had a way of finding villains who were not merely older but aspirational figures to Peter specifically: Norman Osborn, Otto Octavius. The betrayals of those men, those people who Peter could see himself becoming, sting much more than the actual havoc they wreak as supervillains. Marc Webb, who made two flat bad Spider-Man movies, knew enough to return to that mold by starting with a limp yet recognizable Curt Connors.

Second, Peter Parker is an outsider. Because he was raised by an uncle and aunt, he does not fit into the normal family structure that his peers fit into. Because he is brilliant and nerdy, he does not fit into the classic structure of American high schools. (Recent iterations of Peter Parker have a terrible time with a Peter who is highly intelligent now that it’s not socially unacceptable to be preternaturally bright.) Because he does not come from money, he does not fit into the lives of some of his wealthier friends. He must always be an outsider. A Peter Parker who is accepted fits into a group, and a Peter Parker who fits into a group can lean on others for help. As a superhero, that means that Spider-Man is constantly on the razor’s edge. There’s a reason that the Sinister Six and its many iterations throughout the years are so popular in the comics. Peter Parker is not just alone, but outnumbered to boot.

Jon Watts, firmly working within the continuity of a Spider-Man successfully licensed away from Sony and into the warm and crushing embrace of the MCU, is forced to put Spider-Man into a group. By the time Homecoming comes out, we’ve already seen Spider-Man amidst the Avengers, albeit a splintered team in the events of Civil War. The Spider-Man of Homecoming and Far from Home and No Way Home is not strictly Watts’ fault. The Stamper, after all, is definitionally ensconced within a power structure where s/he is not the arbiter of his or her own work. Certainly Tom Holland deserves a lot of blame for the dingy beige interpretation of the character. Watts gets a fair bit of the first part right. Peter Parker is young. Homecoming and Far from Home are both linked to school trips, and No Way Home, hilariously, gets kicked off because Peter has managed to get both his friends knocked out of consideration for MIT. Where Watts fails, and fails unequivocally, is in the more important piece. Spider-Man is never really alone.

In Homecoming and Far from Home, Spider-Man has to manage the villain by himself at the end. Homecoming makes a special point of this, with a scene where Spider-Man, rooting himself on, has to emerge from a pile of rubble that has entrapped him. But to emphasize the final confrontation here is to miss the point. In Homecoming, Peter Parker is still very much under the sway of Tony Stark, who acts as a mentor/pocket god for the teen. At one point, Iron Man has to save Spider-Man’s life, and tells him to put away the costume for a little while. In Far from Home, after Tony sang his last song (“Snappy Days Are Here Again”), Peter is still an Avengers asset, reporting to Nick Fury and SHIELD. This is not a teenager at the edges, someone who is separate from his peers, always a little bit alienated from the world. This is a teenager secure in his popularity and who, in his spare time, is moving as a knight for one of the world’s key chess players. Spider-Man is not alone, caged by the limits of his ingenuity and means. Spider-Man is getting a super-suit from Tony Stark; Spider-Man is getting facetime with J. Edgar Hoover for superheroes. In Watts, it’s difficult to even know what makes Spider-Man meaningful short of his location. Maybe Iron Man or Thor or Falcon or Ant-Man could deal with the problems of the Vulture and Mysterio. They just don’t happen to be in the right place. When Peter was bitten by the radioactive spider, that was an accident. In these first two movies, Watts fails to conceive of a Spider-Man who has grown beyond that initial accident to become an agent in himself.

No Way Home speaks for itself in terms of its failure of considering Spider-Man. Nothing says “I can only look to myself for help” like “I can only look to myself from alternate universes for help,” unless it’s “I can only go to the Sorcerer Supreme for help so my friends can enroll at MIT.” The film set the course for the new MCU. During the first decade of the MCU, we were meant to wonder and stagger in the presence of the crossover. In the second decade, we were too jaded to do that in the presence of the multiverse. Instead, we were given that favorite emotion of fascists: nostalgia. It’s an effective emotion. After Spider-Man 3 and The Amazing Spider-Man 2, you would think that everyone was ready to toss the Maguire and Garfield interpretations off the bridge. It turned out, it seems, that all it takes to make someone miss you is to go away.

Watts’ films are failures, but he’s just what the MCU ordered. He is a consistent presence with a bankable superhero, all the while fitting that bankable superhero into the bankable franchise into the larger bankable franchise. At his or her worst, the Stamper is little more than a company hack, a non-entity making non-movies, a sloshing bucket under the sounds of “Sooie, pig!” Thus Watts.

Jeff Wamester

Justice Society: World War II (2021), Green Lantern: Beware My Power (2022), Legion of Super-Heroes (2023), Justice League: Warworld (2023), Justice League: Crisis on Infinite Earths – Part One (2024), Justice League: Crisis on Infinite Earths – Part Two (2024), Justice League: Crisis on Infinite Earths – Part Three (2024)

With apologies to Matt Peters and Chris Palmer, Jeff Wamester is the defining director of animated superhero movies in the past five years. Wamester’s films feature characters inked into a background, popping up like the segments in pop-up books. It’s a punchy animation style, more welcome in a retro film like Justice Society than it is in work as crowded with people as the Crisis on Infinite Earths trilogy. His movies are purposefully connected to one another, previously an occasional element of DC animated storytelling but now an essential piece of what one is forced to call a puzzle. This results in a shakier command of the material, a carefulness in inserting the details which might matter in future films, a laboriousness. Wamester’s movies have heavy footsteps and deep imprints, and at their worst, just feeling the film raise a foot evokes a wad of gum on its sole. Even the dialogue seems to come slower in his films. Crisis 1 is a serious offender here, with so much space between line readings that you can think about them multiple times before someone else speaks, but other Wamesters aren’t immune to that same problem. Legion of Super-Heroes seems to take an eternity to unfold in exactly the direction you’d expect, while Warworld takes an eternity to unfold into the twenty minutes of plot exposition necessary for Crisis 3.

Watching the three Crisis movies on top of each other translates to 286 minutes, a full forty minutes longer than the Snyder cut of Justice League. It’s an experience much more numbing than engaging, but it’s in those three movies especially where the Stamper expresses himself. Wamester has been given the motherlode to mine, a three-film adaptation of a legendary twelve-issue series that rewrote DC superhero comics and blew a gaping hole in Marvel’s Secret Wars for meaning. What happened in Crisis on Infinite Earths genuinely mattered. The Wamester films don’t earn anything like that. I don’t blame them for that, necessarily. They get just shy of five hours, much of it spent on the the Flash, Psycho-Pirate, Supergirl, and the Monitor, to attempt to bring enough meaning to bear to compare to five decades of DC superhero comics. It’s a losing battle, though Wamester has chosen the ground to fight on. He must adapt, and adapt at length, and in trying to tell a story, too often the Crisis movies lapse into synopsis.

In the first two movies, there’s a lot of time spent on relationships between two unequal but yoked partners. In the first film, it’s Barry Allen and Iris West, whose relationship, wedding day, marriage are all essential in showing us what the Flash must do to give his peers a chance at saving all reality. In the second we see Wamester’s best work. The Monitor lives a torpefied life in his spaceship, witnessing the deaths of civilizations and solar systems and beings perhaps beyond number. He saves Kara Zor-El, later Supergirl, and in doing so the frostbitten hand touches a blue flame. Kara, who believes herself the lone survivor of an entire planet, is catatonic in the face of that disaster, so profoundly physical that it has become existential. What the two of them have is like the relationship of the tutor and the pupil, Chiron and Heracles, something much more intimate than teacher and student. The two of them are bound to one another. As she recovers her sanity and function, he becomes sensitive and engaged. Before Kara, the Monitor may have seen the end of all reality as just another cataclysm to make notes on. After Kara, the Monitor summons extraordinary power to bring as many metahumans and great minds together as possible in order to save life itself. It may be that only these two, interacting in this precise way, could lay the groundwork of rescuing all life from all emptiness.

I’m making Crisis 2 sound like a more interesting movie than it is. It sags with plot in a lot of the runtime (it’s the end of all reality and I’m learning the full autobiography of Psycho-Pirate, do you guys want me to balance a chemical equation while we’re here?), and the execution of the Monitor-Kara relationship is more theoretically interesting than it is anything else. What’s happening is as much faithfulness to the material as Wamester can muster up, and in that faithfulness, encompassing as it wants to be, there are limits. More than even the Crisis movies, Warworld finds those limits and runs headlong into them anyway. A Bat Lash and Jonah Hex story, a Skartoris story, a run-in with White Martians in a story told in black-and-white. It doesn’t add up to as much as a real anthology would, but there’s a lot here, a lot that hadn’t previously cracked the DCAMU lineup, and the movie cynically invites you to see that as reason enough for its existence.

Green Lantern: Beware My Power deserves a word here. For one thing, it’s probably the best of Wamester’s movies, but it’s also noteworthy because it has the opportunity to tell a personal story, and for a little while it seems that the movie might even follow that path. John Stewart, a veteran who has served in Iraq, faced some scary people in battle, done things that I’m not entirely sure he should be proud of, is still so punchy that he can’t go into a convenience store without slamming a normal Joe into the concrete. There’s a lot of fear in him. There is doubt which overrides his will. Yet the ring comes to him all the same, and at first, he tries to shirk the responsibility. This doesn’t last long. It’s important that the hero remains the hero in the world of the Stamper, and without very much development at all, John decides that he wants to keep the superweapon which has decided to bind itself to him. It’s a relatable idea. How many of us would really want to give up superpowers if they were bestowed upon us? In relatability, Beware My Power loses the personal touches of John’s story, and then sees them consumed entirely by the “Emerald Twilight” adaptation that the film speedruns in the second half. Lore triumphs over invention.

There’s a signature in Wamester’s movies more than there is in Watts’, but the essentially lawful nature of one matches the other’s. What makes Wamester less important but more rewarding than Watts is that his work doesn’t sneer contemptuously at cinema as an art form.

Mark Steven Johnson

Daredevil (2003), Ghost Rider (2007)

I ate a lot of pasta and then watched Daredevil and I thought I was going to have to stop the movie and put a cold cloth on my forehead. That sweet 2003 CGI shows us how Daredevil uses his senses to “see” what’s around him, his hearing working as radar that can create a pretty good picture of what’s in front of him. Johnson has the radar vision going, he’s got the flips going, he’s moving the camera, he’s cutting hard, he’s really leaning into a kinetic parkour superhero, someone who we might see in slow-motion only to see in real time a moment later. I think it would have been a little nauseating even if I hadn’t just eaten. Daredevil is not directed well, but if there’s a Stamper path to a new vision of superhero filmmaking, it might well have been hacked out by Mark Steven Johnson.

Johnson is the sole writer on both Daredevil and Ghost Rider, which gives him a level of authorial control on a superhero movie that seems incredible now. It’s not unheard of for a writer-director to get free rein on a superhero movie. We’ve seen it with Christopher Nolan (with brother Jonathan), Brad Bird, James Gunn. But it’s rare. That we have two examples of Johnson’s superhero interpretation where it’s just him is really something. Even James Gunn (allegedly) co-wrote the first Guardians movie. Ryan Coogler was teamed up with in-house Marvel studios writer Joe Robert Cole for both Black Panther movies. Oscar winner Taika Waititi has never had the sole writing credit on an MCU movie. And then there’s the guy whose only previous work as a writer-director was for Simon Birch.

Johnson’s screenplays are bad. The Ghost Rider screenplay has this clanking lorem ipsum quality to it, the kind of movie Wes Bentley at his most addicted to heroin has to laugh convincingly, where multiple characters start by saying, “I know this will make me sound crazy…” The Daredevil screenplay at least has a few laugh lines, although even those bits about alligators in the sewers and fungal infections owe more to Jon Favreau’s ability to say them with his chest than they do to any kind of wit. The movies aren’t any better. If Ghost Rider is water torture, where you have to suffer line by line, then Daredevil is impaled on a structure that feels totally unnecessary. Daredevil starts with a badly wounded Matt Murdock unmasked by a priest. Then we go back to the beginning, back to Matt’s childhood, and then ultimately come around on the events of the movie. Why we need to start with the scene in the church, which is then recapitulated in front of us, is hard to know. My hypothesis? I bet Johnson had the banger of a line “They say your whole life flashes before your life when you die. And it’s true, even for a blind man,” queued up and some executive in the pitch meeting insisted that it should be the first words of the movie.

Both of these movies really challenged my will to live, and although Daredevil is probably the more infamous title, Ghost Rider is the one which had me banging my head against the wall. While we’re talking about people we’ve talked about already: Spider-Man: No Way Home, Justice League: Warworld, and Ghost Rider are all equivalently bad. Get your popcorn and rustle up your icepick for the lobotomy, we’re going to the picture show.

Johnson is not a good director of action, although there’s probably something to be said for the helter-skelter version of combat that he prefers in Daredevil, one where Johnson prizes speed above all else. (A number of DC animated movies, especially those by Jay Oliva and Lauren Montgomery, are more successful in the same vein that Johnson wants to work in.) When young Matt Murdock fights off his bullies after being blinded, he does so with the swift rat-a-tat motions of his cane. When we get our first look at Daredevil as he shows off his moves, it’s nifty thrusts and hi-keeba in front of a dark background. During a fight between Bullseye and Daredevil, Bullseye fires multiple rounds at Daredevil as Daredevil does a series of back handsprings to avoid them. Then it’s all slowed down, the bullets rocketing torpidly at Daredevil’s increasingly ludicrous Silly-Putty body. Speed, either high or low, is essential for Johnson in Daredevil just as it would become essential for the Russos in The Winter Soldier. He may not know what to do, precisely (and I am no fan of the fight choreography in The Winter Soldier, either), but he has an ethos. It’s barely present in Ghost Rider, a movie where things happen slowly. There’s a single sequence where Johnny Blaze is first transformed into Ghost Rider and his motorcycle obliterates a street and sends cars flying into local businesses and lights billboards on fire. That happens fast. But little else does in that film, I’m assuming, because the special effects budget was stretched thin just creating Ghost Rider’s body and igniting his chopper.

Neither Daredevil nor Ghost Rider are especially violent by the standards of the superhero movie. One of the unusual choices that Daredevil makes is that it sets us up for a final battle between Daredevil and the Kingpin, but the fight is short and ends quickly after Daredevil appears to tear a number of ligaments in the Kingpin’s knees. The violence in Ghost Rider is generally left to his chain, which squeezes his opponents into submission. The penance stare, which Ghost Rider uses to defeat Blackheart, is barely violent by the standards of superhero movies. Johnson uses some of the same hazy visual language to show the effect of the penance stare that he used in Daredevil to show off the radar vision. He’s more interested in what the superhero sees then he is in what the superhero punches. Furthermore, his heroes tend to be all or nothing in terms of the violence they deal out. Both Daredevil and Ghost Rider are responsible for kills over the course of their films. If it weren’t for a mid-credits scene in which a hospitalized Bullseye in a full body cast impales a buzzing fly with a needle, you could chalk up two deaths to Daredevil’s vigilantism. Ghost Rider’s killings are of the supernatural kind, eliminating demons. Who would miss a demon or three?

Although Daredevil will come to quibble with his eliminationist approach by the end of the film (“I’m not the bad guy”), neither Daredevil nor Ghost Rider will question that the superheroes in question ought to exist. Ghost Rider ends with Johnny Blaze deciding to keep the curse placed on him by Mephisto even when the devil offers to remove it from the man. Johnny’s rationale is that he wants to fight the devil with the power imbued to him by the devil, a choice which shows Johnson’s intent. No matter how strange or costly the decision might be, the superhero must continue to act even at great expense to himself or others. Even though Johnson’s decisions as a director border on inscrutable, his basic belief in the superhero keeps him firmly within this category.

Peyton Reed

Ant-Man (2015), Ant-Man and the Wasp (2018), Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania (2023)

Something a number of the upcoming Stampers have in common is that their superhero turns come after having made their bones in a subgenre that does not easily mesh with superhero movies. The horror-superhero connection, which we’ll see in James Wan, makes a certain amount of sense. Both genres tend to deal with the supernatural in some way. The romantic comedy-superhero connection requires more steps. In Marc Webb’s case, he might have to walk until his feet are worn down to nubs in order to connect the two. In Peyton Reed’s, even though the Ant-Man movies are as sexless as your average MCU movie, it’s easier to see the screwier side of the superhero movie as translated through the guy that made something as horny as Down with Love.

The Ant-Man movies are probably the most likeable flicks in the MCU. There’s some inherent humor in watching things become the wrong size, the kind of silly, topsy-turvy jokes that we might have expected in ’70s live-action Disney movies. In Ant-Man and the Wasp, the topsy-turviness is brought out of the floorplans and into the streets, which adds to the comedy and makes it the best of the movies in the trilogy. Reed also has a softer touch with his romantic pairings. Hank finds out that Janet has been alive all these years after believing that she’d died, and that he’d had some personal responsibility for her banishment to the Quantum Realm. Reed navigates moments of actual pathos as well as anyone in the MCU, which is to say that he has the command of a guy whose previous film credits were mid-2000s romantic comedies. As any connoisseur of romantic comedies knows, though, casting means the world to credibility. It’s why there’s barely any spark between Paul Rudd and Evangeline Lilly, whose distinct lack of chemistry looms throughout Ant-Man and the Wasp. But it’s also why that Hank-Janet reunion, performed by Michael Douglas and Michelle Pfeiffer, has a spark of reality to it in a world where Pez can be made enormous and then weaponized.

Like Ant-Man and the Wasp, which is still a top-five MCU movie, Quantumania has been savaged by lay audiences and brought to book by critics. Quantumania looks rough, although I think a little too much has been made of M.O.D.O.K. (Not to sound like Todd Phillips here, but the character has always looked ridiculous. It’s sort of like looking at Batman and wondering why he doesn’t have some splashes of neon in his costume…to obsess over what’s obvious misses the equally obvious point.) Nor do I think Scott’s attempts to parent Cassie in the Quantum Realm amount to much, especially compared to how much time Quantumania spends as a cinematic, rather than televised, origin story for Kang. The Stamper cannot hold out against the demands of the brand for too long, and that’s true for Reed in the Ant-Man movies. Two battles with fairly low, almost self-contained stakes yield to something which makes Ant-Man the vanguard of the multiverse wars.

Curt Geda

Superman: The Last Son of Krypton (1996, co-directed), Batman Beyond: Return of the Joker (2000), Batman: Mystery of the Batwoman (2003), Ultimate Avengers: The Movie (2006, co-directed), Superman: Brainiac Attacks (2006), Vixen: The Movie (2017, co-directed)

Geda is a little like Mark Steven Johnson in that I didn’t think it was possible for a director, least of all a Stamper, to make movies in the shape that he did. There used to be a time when you could have a superhero television show that was really separate from the movies that were coming out around it. Nowadays, that superhero TV show can either be aggressively distinct from your superhero movies, or you can try to make the two of them absolutely inseparable. Brainiac Attacks was made two years before The Dark Knight and Iron Man, but at its heart it has more in common with Batman 1966 than it does with either of those two movies. Expressly cartoony, as all of Geda’s work is borrowed from the proverbial Saturday morning cartoons, Brainiac Attacks is made for children. If the Lex Luthor of Brainiac Attacks has anything to say about it, the movie is really for weird children. Powers Boothe voices Luthor like he’s George Hamilton three martinis in, and he’s drawn to be equivalently tan. At this point in my life I’ve seen supervillains in many, many different ways, and I can confidently say that there is no villain in a superhero movie quite like Lex Luthor here. This is not to say that the movie is good. Quite the opposite. Brainiac Attacks is almost unbearably repetitive, like Blue’s Clues but with more punches and explosions. That replication issue is present in Mystery of the Batwoman as well, where, shocker, it turns out to be three separate Batwomen as opposed to a single woman in a single costume on a single glider.

The most interesting decision made in a Geda movie is in the characterization of Bruce Banner in Ultimate Avengers. Like the original Avengers story from the comics, the unification of the Avengers comes primarily from having to contain the Hulk from doing terrible damage. The movie feints in the direction of a Chitauri invasion, which is not all that interesting. The groundwork it laid in characterizing Bruce Banner at the beginning turns out to be what’s essential, and it’s this characterization of an individual which stands out not just in Geda’s work, but in all representations of Banner/the Hulk in movies. For this film, in which Geda is part of a three-man team with Steve E. Gordon and Bob Richardson, Banner is on drugs in order to keep him even. There’s a little bit of Next to Normal in Banner. Medication is keeping him from becoming the Hulk, but it’s also stripping his mind, keeping him from the breakthrough with the super soldier serum that he’s been assigned to recreate. He is a shell of a man, dyspeptic and drawn, and as much as he knows he cannot return to the Hulk again, he is withering away having to be, for lack of a better word, himself. All hell breaks loose when Banner finally gives way, and although the movie ends with the Avengers assembled and ready for further action, that despair that Banner must feel has to be remembered. For Geda and company, the Hulk is an ironic figure, his genius linked with his monster, forced to live within bounds which make others safe and make him miserable. He’s not just on the treadmill, like Spider-Man or Batman. Theoretically, those guys could step off at any time and accept lives as a brilliant research scientist with a hot girlfriend, or a billionaire with a lot of hot girlfriends. Banner can never step off the treadmill, but he’s never allowed to run, either. We’re about as likely to get a character like that in a major superhero movie as we are to return to the Saturday morning cartoon as a primary vessel for superhero consumption.

The Stamper without a strong heroic figure to highlight is in an odd spot indeed. Style becomes more important. I love the cyberpunk look of Neo-Gotham in this movie, its discotheques, the contradiction between the old Batcave and the old candy factory against the rest of a city with hovering cars and laser handguns. There’s a good case to be made that no Batman movie does a better job with color than Geda’s Batman Beyond, which finds strength in cels which might only have two or three colors total. You can feel Geda striving to convince us that Terry McGinnis is Batman in this movie on top of delighting us with the look of Neo-Gotham. The movie can’t do it, and while I never watched the show as a kid, I kind of doubt that the television show could have convinced us of Terry’s Batman-ness. They may wear similar costumes and have similar gear and fight similar villains, but those are all superficial. They’re just not the same guy. How am I supposed to believe that a guy named “Terry” could be Batman, anyway?

This is one of the fundamental issues of a superhero who is popular enough to bridge generations. From a business perspective, Batman is non-negotiable. The fans want the creator to give them Batman. The bosses will arrange to have the creator shot if s/he doesn’t give them Batman. And for all I know, the creators may want Batman as much as the fans or the bosses. But Batman Beyond wants to have its cake and eat it, too. It wants to use the many shorthands of Batman as we know him, but it doesn’t want to be stuck doing the same thing as its predecessor, Batman: The Animated Series. Thus we get a void at the center of the film. This may be Batman, in some sense of himself. But it’s not Batman as we know him. Bruce Wayne makes sense, in no small part because we know how Kevin Conroy sounds in the role. Terry McGinnis doesn’t make sense. There are multiple mentions of Nightwing, which is a little frustrating because Terry has much more in common with Dick Grayson than he does with Bruce Wayne. Terry is not one of the Robins despite filling the same role as they did. The final confrontation in Batman Beyond is between Batman and the Joker, which, same as it ever was. But they’re not the same people. It’s not Bruce and the Joker. It’s Terry and this weird mutated remnant of the Joker that’s using Tim Drake’s body. There’s no history between these people, which the Joker comments on a few times, and every time he does, the fight sags a little bit more. These are strangers to one another.

Chris Palmer

Superman: Man of Tomorrow (2020), Batman: The Long Halloween – Part One (2021), Batman: The Long Halloween – Part Two (2021)

Palmer has an easier style to ingest than Wamester’s, although the two of them are working from similar models. The Long Halloween, split into two parts and running a little shy of three hours, is a thorough retelling of the graphic novel of the same name, and there’s some tedium in the storytelling not unlike what we see in Wamester. Given how much Palmer’s work seems caged in by the demands of the DCAMU (of which Man of Tomorrow kicks off a phase) and the Long Halloween adaptation, I have a hard time putting him anywhere else. It’s possible that if Palmer adds more films to his superhero CV that he might end up in a different category. Even in Man of Tomorrow, the night has a brooding quality to it, a nuclear plant’s warm glow spreading into the atmosphere against the blacked out silhouettes of the city nearby. That quality is amplified, obviously, in The Long Halloween movies, which deserve a place among other superhero movies with a dark palette.

I’m curious about Palmer more than I am about any of the other directors in this group. The Tomorrowverse phase of the DCAMU is split entirely between Palmer and Wamester. Palmer handles the majority of the standalone stories, while Wamester is the one who is forced to handle the ties between movies. Unsurprisingly, with a more standard plot structure on his side, Palmer by and large has the better movies. How much that has to do with Palmer as a director I’m not sure, and I wonder if the visual flair he wanders into in The Long Halloween has more to do with a recognizable adaptation or more to do with his own sensibilities.

James Wan

Aquaman (2018), Aquaman and the Lost Kingdom (2023)

I’ve already hinted at the way that horror and superheroes have a natural place to cross over, and Wan’s work in the past has given him two ways to get there. First, as the director of Saw, it’s easy to imagine a superhero movie which pushes into the real of psychological horror. Batman has gotten close to torture porn before; couldn’t Wan push him over the edge? Second, as the director of The Conjuring, the supernatural, the express proof of something which we cannot totally comprehend but must reckon with all the same, Wan has plenty of relevant experience.

Naturally, neither of his Aquaman movies really let him lean into those horror manifestations. There’s a jump scare in Aquaman, and in both movies there’s some creature design that looks like it could have come from horror, but for the most part they both work as comedies with Jason Momoa playing a slacker god. In Aquaman, Arthur clashes with mission-oriented Mera; in The Lost Kingdom, Arthur clashes with chivalric Orm. In animated movies, they’ve made a point in the past decade of pointing out that Aquaman is possessed of almost godlike powers. In live-action movies, they’ve let Momoa’s muscles do a lot of the talking while working in the other direction. Rather than trying to put us in awe of Arthur, we are meant to chortle at his oafishness. (In MCU terms, we might call this “having your Thor and eating it too.” Alternately, the special effects in these movies are both just awful, and maybe they decided it was better to act like everyone was in on the joke of the special effects together? I dunno. They really do look bad.) The humor in those movies is unsatisfying no matter how competent Wan-regular Patrick Wilson is. Yet Aquaman is, for all of these flaws, among the very best of the DCEU movies. They gave a blockbuster movie to a guy who has made plenty of blockbuster movies, and it feels like a blockbuster movie. If it’s pretentious, it’s pretentious in service of its humor and its attempt to put the comic back in “comic book,” from Arthur’s insistence that he could have just peed on an object requiring water to work, to the ridiculous Day-Glo hair they gave Amber Heard.

Given that the DCEU is dead, I doubt if we’ll see Wan back in the fold, let alone for an Aquaman movie. To me, this makes him among the most tempting and reasonable free agents for Marvel or DC, especially if anyone, someone, were to combine two hugely popular genres. One of the presumptions of horror is that given some situation, certain people will be absolutely helpless. It’s true in the superhero genre as well. Surely someone could give James Wan the leeway to recreate The Conjuring (endangered group reaches out to knowledgeable figures who cannot wield as much power as what endangers the group) but with superheroes. Under those circumstances, there’s no director named in this post who I’d rather see helming another superhero movie than Wan.

Joe Johnston

The Rocketeer (1991), Captain America: The First Avenger (2011)

Johnston has made two of the more enjoyable superhero movies of the past forty years, and he’s done so in a way that’s so simple that it’s practically genius. All you have to do is set the action of your film during the years around World War II and the audience just cries out for a hero. He does not have to challenge the gods for might, because all he’s doing is fighting Nazis. Cliff Secord is not Thor or Superman or the Hulk. He’s not even Iron Man. Cliff has a jetpack and the Nazis don’t and that’s good enough to go on. The hero just has to be a handsome white fellow with a good jaw, no recognizable accent, and look good in whatever costume you stick him in. Neither one of The Rocketeer or The First Avenger is an especially good movie, but they are what so many superhero movies are not: watchable. What makes them watchable is what makes them average, as far as that goes, as not even the old Hollywood movies people think they know about ever thought that a white guy with a square jaw was absolute cinema. Johnston’s work has a refreshing disinterest in lore and, even if the special effects in both movies are a little hairy for a guy who cut his teeth on Star Wars, they appear to the eye without infringing too much on our sense of reality.

Ethan Spaulding

Batman: Assault on Arkham (2014, co-directed), Son of Batman (2014), Justice League: Throne of Atlantis (2015)

Spaulding pushes the edge with violence a little bit more than most of the other people in this group. The League of Assassins, primarily armed with swords, are gunned down by adversaries firing from the air. There’s some electrocution in Throne of Atlantis which puts Billy Batson in some grave danger and which sees Cyborg put down for the count in an upsetting way. But Spaulding, despite working closely with top Brute Jay Oliva, doesn’t quite make it there himself. If anything, there’s a humor in Son of Batman that makes it more than palatable, while the lack of humor in Throne of Atlantis makes it close to unwatchable. Maybe Aquaman’s sideburns are the joke? The guy has muttonchops like I haven’t seen since I watched Woodstock.

Damian Wayne is not quite at his most annoying in Son of Batman, but the audience for this movie is made up of people who, if Batman said to jump, would get on a pogo stick with Batman bumper stickers and attempt to take flight. Any kind of resistance to the sacred law of Batman is received with disbelief, and Son of Batman takes that concept to extremes that, arguably, no hero ever goes to. All the same, just because Damian takes a while to get used to the whole “no killing people” thing doesn’t mean that he doesn’t ultimately accede to the “no killing people” thing. At one point he has Deathstroke under his sword and refuses to strike the final blow because Batman has taught him not to. Batman gets an in-house challenger like we’ve never seen him have in a Bat-movie, but for as much squealing as precedes it, it ensures that Deathstroke will be a menace for all time.

Marc Webb

The Amazing Spider-Man (2012), The Amazing Spider-Man 2 (2014)

I know I’ve used sharp words to describe the work of some directors, and I think that’s okay. That’s what the money is for. I struggle to know what to say about Marc Webb’s superhero outings because I think I would cross the line between “sharp” and “mean-spirited.” I like the Peter Parker-Gwen Stacy connection. I don’t think it has the juice that Peter and MJ have because Peter and Gwen, absent Gwen’s neck breaking, could only ever have a copacetic relationship. Gwen could never say “Go get ’em, tiger,” to Peter, but hey, nobody’s perfect. It’s an interesting choice to set Peter up with Gwen rather than MJ, and I like that. Not every Spider-Man adaptation has to have the same characters. Andrew Garfield and Emma Stone are both very good-looking, they were both good actors in 2014 even if neither had made a true star turn, it seems like it’d be hard to mess it up. Leave it to Marc Webb, but these movies, centered on the relationship between Peter and Gwen, are messed up.

You can see them on screen, you can see the smiles, the kisses, the cuddling, and you know it’s supposed to be alluring, but what’s alluring about it has absolutely nothing to do with Peter and Gwen and absolutely everything with having two models in front of the camera. Marc Webb simply has no idea how to make those people feel like people to us. There was a lot of press about how Garfield and Stone were together at the time, and that’s when people start to say “Oh, they’re really into each other in real life, it’s a window!” but mean “Oh, I’m not getting anything from this, maybe I will if I fool myself into thinking it’s real?” Good luck out there to Tom and Zendaya!

Brutes

Jay Oliva

The Invincible Iron Man (2007, co-directed), Doctor Strange (2007, co-directed), Next Avengers: Heroes of Tomorrow (2008), Green Lantern: Emerald Knights (2011, co-directed) Batman: The Dark Knight Returns – Part One (2012), Batman: The Dark Knight Returns – Part Two (2013), Justice League: The Flashpoint Paradox (2013), Justice League: War (2014), Batman: Assault on Arkham (2014), Batman vs. Robin (2015), Batman: Bad Blood (2016), Justice League Dark (2017)

In Black Adam, there’s an exchange that’s meant to be funny, and I suppose could have gotten there if Dwayne Johnson weren’t the one pounding the dialogue into our ears like a nail gun pounds a 2×4. “I do not want you teaching him violence,” a woman tells Teth-Adam, trying to protect her son from the Kahndaq superman. Teth-Adam replies, “Who do you want to teach him violence, then?” Jay Oliva made all of his movies in the sample before Black Adam was made, but that line encapsulates his work. These are movies about people who have been taught violence, and that violence is absolutely necessary both to the endeavor of the superhero and the endeavor of the director. Indeed, a world where superheroes do not work primarily in the genre of violence is unthinkable.

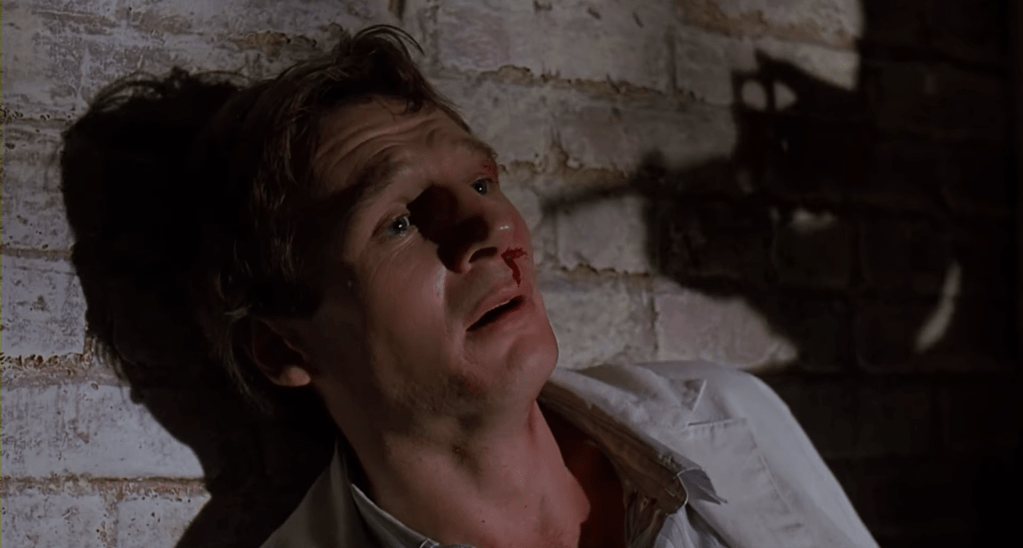

I had an epiphany watching The Dark Knight Returns – Part One, while Batman is in that mudpit operating table with the leader of the Mutants. Some people watch superhero movies because they like watching one person beat the shit out of another person. Maybe it’s even most people watch superhero movies because they like the spectacle of one person beating the shit out of another person, or one person beating the shit out of many people, or whatever variation is at hand. That has to be the appeal of that scene, recreated from the Frank Miller comic, right? If you do not enjoy the spectacle of two large, broad-chested, powerful, fluent with left and right hooks alike, leg-sweeping, nose-busting, slow-bleeding people, then what could possibly be the appeal of that scene? Oliva understands that we’re here for that pummeling more than we are anything else. It’s not action that moves us. It’s violence, violence that Oliva delivers by pummeling us frame by frame with it, violence that needs neither rhythm nor grace to enrapture us. That sequence in The Dark Knight Returns – Part One is the first one I would show someone who wanted to understand what the superhero movie is about. On one side: justice. On the other side: chaos. How do we resolve the two? Put chaos on the operating table and let justice take it apart. Oliva simplifies the entire genre into a few sounds, a few motions, a single purpose. Form follows function. Oliva places the camera where it best emphasizes the violence. If bones crack, highlight the shape of them breaking. If blood trickles, capture its descent. If a face is rearranged with the force of a punch, then follow the ebbs and flows of those elastic features.

If his movies were better, I’d call Oliva a genius. In the absence of that kind of quality, I’ll settle for calling him the best and most important director in the genre. There is no superhero without the habitual use of such violence that would rupture our dreams if we just saw it one time. That is what the superhero offers to us, provides as a service. No matter what we are told by our parents or in school, we want our problems to be solved with violence. We fantasize about striking others. We chase after footage or, better yet, real-life expressions of violence in fights. We love violent sports where physical injury is part of the game, and where long-term health problems are part of life after retirement. We come up with reasons that protesters or civilians deserve life-altering and life-ending forms of violence at the hands of some superior armed force. We believe that a problem solved with violence is permanently ended, that it sends a message that a peaceful resolution does not. Oliva understands these principles, and his movies are not there for the viewer to watch so much as they are weapons for him to wield. He is locked into those fantasies, and more than that, he translates those fantasies into entertainment. This is the stock in trade of the Brute. S/He recognizes the true element of the superhero fantasy. It is not “What if I were more powerful than my peers?” or “What if I were able to help far more people than I can now?” or even “What if I were idolized by the masses?” The true element of the superhero fantasy is “What if I was supposed to make things right, as I saw them, by means forbidden to others?”

Four of twelve Oliva efforts are expressly about Batman. (Batman: Assault on Arkham and Justice League Dark both lean on Batman as a key character, but I wouldn’t say either one is really a Batman movie.) No superhero is more perfectly connected to the true superhero fantasy, and no director short of Christopher Nolan has opportunities to discover Batman like Jay Oliva.

All together now: I’M NOT WEARIN’ HOCKEY PADS.

Through his wealth and his vast resources, through his years of training, through his cunning, Bruce Wayne is living the superhero fantasy that so many viewers crave. None of us can really imagine what it would be like to be Superman or Wonder Woman, but all of us can imagine what it would be like to live as Batman. Some of us have even spent time in boxing gyms or at karate classes. Batman, as plenty of movies have reminded us, is a guy in a costume. I am sure it was Joss Whedon and not Chris Terrio who insisted on the line from Justice League where Bruce explains his superpower: “I’m rich.” He is not a metahuman like Flash, not gifted a power ring like Green Lantern. For that reason, Batman is the superhero most like an officer in combat. His pugilism, while laudable, is inferior to his strategy. When Batman succeeds, it is because his strategy succeeds, because the manner in which he lives his role has been adequate to the challenges faced by it. When Batman fails, it is rarely because of some failure with the Batmobile or whatever gadget he’s pulled off his gadget belt. It’s a failure of Batman’s strategy, a rare failure of imagination or foresight.

Other directors have approached the question of whether Batman’s ethos of vigilantism—anything short of direct killing is acceptable—is workable or desirable, and all of them basically give him the thumbs up. Sam Liu gets the job of Batman: The Killing Joke, and ends up watering it down with a cringy first act in which the teacher (Bruce Wayne) sleeps with his student (Barbara Gordon). Christopher Nolan is fine with a Batman who violates all norms of conduct with noncombatants (spying on civilians with tools that the Stasi would kill for) as long as he feels sorry about it. Brandon Vietti, as we’ll come to soon, gets this close to criticizing Batman in Batman: Under the Red Hood and then walks it back. Oliva, however, has the mother of all Bat-texts. He has both parts of The Dark Knight Returns, and there is no superhero hagiography quite like that story, no story which, to borrow from the parlance of the youth, “glazes” its protagonist with such zeal.

The Dark Knight Returns, in both parts, recognizes the common critiques of Batman. For one thing, he works outside the law, has no legal authority to fight crime, and so is an outlaw. So says Commissioner Yindel, Gordon’s replacement at Gotham PD. Batman has a symbiotic relationship with the various rogues he has fought and captured. So says psychologist Bartholomew Wolper, doctor to the Harvey Dents and the Jokers of the world. The movies don’t take either of those critiques seriously. For all of Yindel’s attempts to collar Batman and bring him to justice, she cannot control the major gang on the streets, the Mutants, nor can she bring criminals to heel at the requisite rate. On the other hand, after there’s a baby nuclear winter in Part Two, Gotham becomes the safest city in America because Batman basically takes over a remnant of the Mutants and uses them as law enforcement. Harvey Dent tries to blow up a building in Part One, and in Part Two, a previously catatonic Joker comes back to life and does some nasty mass killings. People tried to bring them back to health, but something about those characters simply rejected that kind of help. In administering plastic surgery to Dent and fixing the exposed side of his face, all the doctors did was make him believe he was disfigured on both sides. The Joker is too broken to fix. As soon as he gets the opportunity, he’ll kill anyone just to get his kicks.

You can’t fix crime with better policing. You can’t fix Harvey Dent by giving him his face back. You can’t fix the Joker by putting him through treatment. You can only fix these problems with Batman, and more specifically, with Batman’s fists. In Part Two, Batman breaks the Joker’s neck enough to paralyze him, though not enough to kill him. The movie does not linger on this particular moment of moral crisis in which Batman wants to kill the Joker but doesn’t do it; he gives in just enough to do irreversible damage to his nemesis instead. It seems like this would be an appropriate time to reflect on where the line is for Batman. Is paralysis closer to what Batman usually does, or is it closer to killing? Would the Batman of The Dark Knight Returns be justified in paralyzing multiple other individuals, especially criminals as dangerous as Harvey Dent? The movie dodges this issue entirely. The Joker, that goofy galoot, twists his neck hard enough to kill himself, knowing Batman will be blamed. You can only protect other people from the Joker by paralyzing him, the movie finds. The Joker is so twisted that paralyzing him can’t protect him from himself. Violence is the answer in both halves of The Dark Knight Returns. It ends the threat of the Mutants. It brings stability to Gotham while the rest of the world falls apart. It proves that Batman can defeat Superman with a little help from some kryptonite and Green Arrow, giving the lie to Ronald Reagan’s post-nuke propaganda. There’s something of the witch-ducking in The Dark Knight Returns. The test is that Batman will beat you. If you pick yourself up and do good, he was right to beat you. If you pick yourself up and do bad, he was right to beat you.

Oliva’s most violent movie is not a Batman movie, incredibly. No matter how violent the Dark Knight Returns movies are, and regardless of their basic belief in the justice of violence, they still cannot compare with Justice League: War. Not only is War the most violent movie in Oliva’s oeuvre, but it is more violent than any movie by Steven Spielberg, Rob Zombie, David Fincher, or John Carpenter. War has more in common with Bone Tomahawk than it does with anything Jeff Wamester ever made.

War has essentially the same barebones plot as Zack Snyder’s Justice League, but in under ninety minutes it stacks more violence than Snyder does in four hours. The Justice League comes together rapidly, with minimal character introductions. Cyborg and Shazam show up together. Flash learns who Batman is after briefly reconnecting with Green Lantern. Wonder Woman and Superman show up. Parademons sent to Earth via boom tubes flood the skies and fill the streets. The battle takes place at night. The city has no personality, and the streets are basically deserted before most of it is Beruitized. Eventually Darkseid himself comes through the portal and personally wreaks havoc. You could spend a full day trying to categorize the types of blows that the characters strike in War: by superhero, by parademon, by Darkseid, by fist, by weapon, by superpower, against friend, against foe, damage-inflicting, disabling, deadly, by amount of blood, by amount of concussive force, by amount of explosive force. The action is quick, but not so quick that you can’t savor each attack.

The superhero movie frequently pits the hero or heroes against legions of enemy combatants. The parademon, winged soldier of Apokolips, each one shanghaied and genetically modified to become one of Darkseid’s pawns, is the best example across superhero movies. They are in every movie with Darkseid, and even appear in Justice League, which Darkseid is technically not in. The parademon is armored and stronger than any man. In some cases, it breathes fire, while in others, it comes with firepower. OIiva prefers the fire-breathing parademons in War, and he unleashes swarms of them on the Justice League: Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, Flash, Green Lantern, Cyborg, and Shazam. The heroes are kept very busy but not necessarily overwhelmed by the parademons, many as they are. The primary battle is fought in the city by the latter heroes, but there is a secondary battle on Apokolips, where Superman is brought after being captured and Batman puts himself at risk to rescue him. Superman is not all the way himself after nearly being turned into a parademon; he kills Desaad. Superman does not kill lightly, but in War, he does so, choosing not to lash out, when he does lash out, against the hordes, but against their maker.