This is the second part of a three-part series. The first part, where I talk about the superhero genre’s place among other quintessentially American film genres, is here.

The Best of the Fourth Genre

What I was going to do here, in the interests of giving you the wisdom of crowds and critics, was one of those meta-analyses I like to do. The problem is that the pickings for the superhero movie list are pretty thin! For one thing, any list that’s more than a few years old feels hopelessly outdated. For another, multiple outlets admit that there aren’t many movies to choose from compared to older genres like western, horror, and sci-fi. I have no proof of this third guess, but maybe outlets don’t want to subject themselves to the withering critiques they’ll get from the superhero crowd, which has earned a reputation for sexism and racism based on review-bombing campaigns and online presence.

As far as talking about which superhero movies are actually good…you’re locked in here with me. Here’s a complete list of every superhero movie I’ve rated 4 stars or higher on Letterboxd. I’ve arranged these by date of release. It’s a short list.

- The Incredibles – 2004, dir. Brad Bird. 4.5 stars

- Batman – 1966, dir. Leslie H. Martinson. 4 stars

- Unbreakable – 2000, dir. M. Night Shyamalan. 4 stars

- Spider-Man 2 – 2004, dir. Sam Raimi. 4 stars

- Justice League: Crisis on Two Earths – 2010, dir. Sam Liu and Lauren Montgomery. 4 stars

- X-Men: First Class – 2011, dir. Matthew Vaughn. 4 stars

The Seeing Things Secondhand 4.0 Crowd

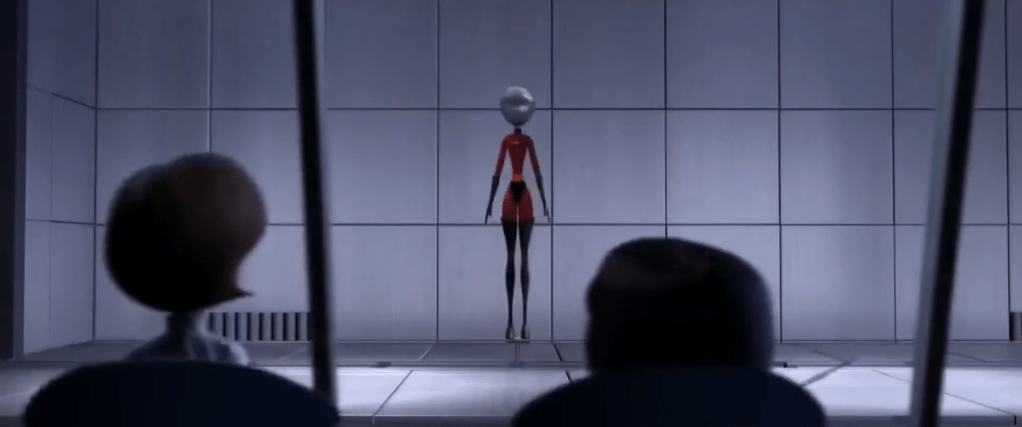

The Incredibles

In the first few minutes of The Incredibles, Mr. Incredible does a number of amazing things. He rescues a cat from a tree. He uses the tree the cat was stuck in to end a car chase between some crooks and the cops. He intercepts a man jumping off a building. He stops Bomb Voyage from a successful burglary. In stopping Bomb Voyage, one of the villain’s explosives lands on a train track, and Mr. Incredible successfully prevents the loaded train from crashing. In the days that follow, Mr. Incredible (and thus the American government, which has been holding itself liable for the actions of caped crusaders) are sued by the man whose suicide was interrupted, for pain and suffering inflicted upon being rescued. The tracks that Mr. Incredible partially obliterated need to be replaced. And in the days which follow those, superheroes are legislated out of existence. “It’s time for their secret identities to become their only identities.”

Watchmen is the superior superhero story. I’m not sure it can be eclipsed. Watchmen is like the collected works of Stephen Sondheim. On a factual level, there are other comic books, there are other musicals. On a real level…no, there aren’t. There’s Watchmen and then there’s everything else. Watchmen is the proof that genre matters. What does it mean to be an augmented human? What does it mean to fight on behalf of a just cause? What are the problems that a normal person can solve, and what are the problems that a superhero can solve? Watchmen takes a scalpel to every single one of those ideas, puts them under the microscope, demands our attention. If there were a superhero movie as good as Watchmen, there would be a superhero The Godfather already. But there isn’t, more’s the pity. The closest we have to Watchmen is The Incredibles.

What does it mean to be an augmented human in the world of The Incredibles? Mr. Incredible, Elastigirl, Frozone are like Wolverine: their powers are unexplained, and more than that, probably heritable. Augmented humans are able to pass as normal in everyday life. There are no Nightcrawlers or Beasts whose mutations make them unable to pass as human in line at the bank. The superheroes of The Incredibles have the best of both worlds, able to appear normal while able to do the extraordinary. Villains in The Incredibles work at a disadvantage. Instead of being naturally gifted, they must do villain-of-the-week kind of things (fool around with nuclear warheads, rob safes) with their everyday abilities. Syndrome, who builds himself into being Mr. Incredible’s nemesis after being his ward, is the best of the villains. Like Batman, he is not superpowered, but like Batman, he commands technology that can, at its best, replicate the experience. Unlike Batman, Syndrome craves publicity and fame, and really unlike Batman, he intends to make sure that his technology gets in the hands of the public at large so that “when everyone’s Super, no one will be.”

The Incredibles has the gall to ask a question which many a wit has posed, but which virtually no superhero movie wants to address. Does the presence of superheroes cause the presence of supervillains? The answer is yes. Supervillains and dastardly types abound enough during the age of heroes so that there can be a great number of them, forming loose collectives and in some cases actual teams. Then, once superheroes are outlawed, there’s no record of any kind of supervillain or extreme threat that can’t be handled by law enforcement. Even Mr. Incredible recognizes that there’s nothing permanent about what he does, that all of his exertions seem to count for nothing. “I feel like the maid,” he tells an interviewer. “I just cleaned up this mess. Can we keep it clean for ten minutes?”

Bob longs for the glory days of being a superhero much as the high school quarterback yearns to get back on the gridiron, and when he gets the opportunity for hero work again, he sees that like an open tryout for an NFL practice squad. The film casts this decision as a moral failure. He’s made a pattern of lying to his wife (he and Lucius “go bowling” when they’re in fact listening to police scanners and trying to bust criminals), and his new hero work drives him joyfully into lying about becoming more important at work. The world doesn’t need Mr. Incredible to come back. Bob Parr needs Mr. Incredible to come back, and by throwing himself into what he believes to be hero work, Bob helps to crystallize Syndrome’s plan to pose as a superhero himself.

There’s a scene in the movie where Mr. Incredible has hacked his way into Syndrome’s computer and can see that Syndrome’s robot has killed a number of supposedly retired Supers. Each of those superheroes aching to return to the job, all of them just as arrogant as Mr. Incredible, help to finetune the machine that Syndrome is going to use to villainously. They make Syndrome a better villain, a more powerful man, molding him into the version who will descend upon the city and “rescue” them from the robot. Mr. Incredible is the final test for Syndrome, the greatest of them all, the one he most needs to conquer, and Mr. Incredible falls into the trap not just as a sucker but as a stereotype. Mr. Incredible and Gazerbeam and Universal Man and the rest believe that they are solutions to problems because it makes them feel good. Bob Parr, an insurance representative, wants to go back to being on the cover of magazines, wants to go back to fan clubs made in his honor. He wants to go back to a world where there are no negative consequences for his actions, playing a video game where it’s always on an easy mode. There are ways that an unnaturally strong human being could continue to be of service to his fellows without attracting attention to himself, if that were his goal. But it’s not Bob Parr’s. The Incredibles is a movie for children, and it ends with homilies about the importance of family…but the importance of the family, in the end, is that it gives Mr. Incredible a team of superheroes with which he can cavort and do wonders before the closing credits. (“I’m the Underminer! I am beneath you, but nothing is beneath me!…”)

The superhero film makes this choice almost every single time. The Incredibles is unique because it spends most of its runtime critiquing the concept of the Super, rather than making little nods toward critique here and there. This is a genre convention, after all. The superhero is engaged in the fight for goodness, and he must express himself violently in order to bring about a state of peace. It’s only natural that The Incredibles takes the direction of bringing the entire Parr family into hero work now that the kids can control their powers to do violence to evildoers and rectify dramatic situations. In the western, it was only natural to see the Ringo Kid elope with Dallas so that they might become neighbors to the Edwards family and help to civilize Texas. What “civilizing Texas” means is loaded, just as loaded as a pair of retired superheroes deciding to put their children in harm’s way to act as vigilantes.

Justice League: Crisis on Two Earths

Now feels like a good time to revisit the question of jurisdiction that’s brought up in Crisis on Two Earths. In the first instance where the Justice League might be said to overstep their bounds, Superman and Wonder Woman agree that where there is injustice being done, the Justice League has a responsibility to intercede. If you’ve ever felt uncomfortable with the idea that America’s military acts as “the world’s peacekeeper,” imagine how uncomfortable you’d feel if the American military decided to intervene on Mars. What the Justice League does is even more audacious than that. Militaries are (theoretically, ha ha hee hee) accountable to established international law. There’s nothing like that for superheroes in Crisis on Two Earths, and this small group intends to interdict the efforts of a like small group based on the testimony of one escapee. Green Lantern even expresses some discomfort because he sees himself as a “beat cop,” and other Earths are definitely not his beat. As we’ve already covered, Batman objects to the attack on the other Earth, and objects on the principle that they have a responsibility to their own Earth. It’s a statement almost as enormous as Superman’s, nearly as sweeping in establishing the godhood of the augmented. At the time the movie starts, the Justice League are putting the finishing touches on a space station that Bruce Wayne is paying for in order to better surveil and meet the needs of Earth. I promise I’m not trying to be funny with this comparison, but seriously, if you ask your average Christian theologian, that person will tell you that Jesus Christ isn’t going to save everyone. Batman and company are placing the responsibility for the safety of humanity on their own shoulders, and when the Lex Luthor of an alternate Earth stops by and asks for their help in guaranteeing the safety of another humanity, Superman doesn’t even blink.

Given the enormity of Superman’s decision at the outset, it’s kind of less surprising that the Justice League decides that they will not act in accordance with the wishes of the president of this alternate Earth. The president has an uneasy truce with the Crime Syndicate. They allow him to keep the government intact, and in return he does not seek to curtail their flouting of the law. Based on the fear of the Crime Syndicate, people already do not want to cross them, witnesses don’t want to testify, lawyers don’t want to prosecute, and so on and so far. We are meant to see the president’s decision as a pusillanimous one. It’s certainly not bold, and his decision to release Ultraman back into the wild after Lex Luthor and Superman worked together to get him in the paddy wagon is vexing. Still, the irony must not be lost on us that at this moment in the film, there are two superpowered groups, neither of them is listening to the president, and only one of them came from another planet in order to do that. The Crime Syndicate promises that it will exploit the American people. The Justice League promises that it will invade, declare its own form of martial law, and then go back from whence they came. Can we blame the president of this alternate Earth for his leery reaction to the Justice League’s recommendations? We are meant to, certainly. Crisis on Two Earths is not abashed about the principles that The Incredibles at least blushes about for show.

Crisis on Two Earths has a supervillain death. There are multiple fatalities caused by the Parr children in The Incredibles. These are unusual circumstances, for as a general rule, the superhero does not kill. How far the superhero will go towards killing is what complicates our conception of him or her, what might shade in an otherwise heroic figure. That line from The Dark Knight Returns – Part 1 where Batman says this is an operating table and he’s the surgeon summarizes a lot of superhero combat. Because the vast majority of them are against killing, you have to believe that these superheroes are holding back a little bit with their punches, keeping their phasers set to “stun,” whatever. Watch Cyclops in any X-Men movie, and you recognize that there’s a difference between what his eyes are doing when he’s fighting people and what his eyes are actually capable of doing. I don’t know what Wolverine’s body count is in every movie he’s ever appeared in, but even for a character who is set up to be a perfect hand-to-hand killing machine, a lot of those people are presumably just “knocked out” as opposed to dead. Deadpool, on the other hand, makes a show of not playing by the rules that other superheroes have to play within. In a way, that early sequence in Deadpool & Wolverine where he kills a lot of NPCs is a statement of principle just as much as Batman’s refusal to kill is a statement of principle. The treatment of threatening human life is much the same in both heroes. Deadpool goes a few steps further and finishes the job that Batman never does.

X-Men: First Class

What makes X-Men: First Class special is the scene towards the end where Erik gets his revenge on Shaw. Shaw, then a Nazi officer, met Erik in his youth, and killed Erik’s mother in order to unleash the boy’s magnetic powers. As an adult, Erik goes from place to place, finding people who were connected with his mother’s death in some way, seeking out Shaw, and killing ex-Nazis along the way. Watching people kill Nazis may have reached its apex with Raiders of the Lost Ark, where we watch heads explode and blood splatter, but of course the pleasure of seeing Nazis gunned down, stabbed, thrown of trains, blown up, etc. is a much older one. Alfred Hitchcock knew how satisfying it was to see individual Nazis killed. So did Carol Reed. Sahara, made by a true showman in Zoltan Korda, provides a double pleasure. Not only do Humphrey Bogart and company kill a bunch of Nazis, but the Nazis are also about to die of thirst. Casablanca, about as romantic a movie as was ever made, realizes that watching Rick and Ilsa say goodbye to each other for the last time can be made that much sweeter by knowing that their shoes are wet with Major Strasser’s blood. Sebastian Shaw is not your average Nazi, I suppose. He is not faceless, as the many Nazis of Sahara and Raiders are, and he is not ratlike, like Norman Lear in Saboteur. He is brash and powerful, never shy about using his powers for his own betterment, and when the Nazi government falls, “Klaus Schmidt” transitions to “Sebastian Shaw” without handwringing.

Matthew Vaughn hadn’t made Kingsman: The Secret Service when he made X-Men: First Class. The Secret Service has one of the most violent scenes I’ve ever come across in a live-action movie. Colin Firth goes into a church, the secret violence music starts playing, and within a minute, Firth’s character has shot and killed twenty people at point blank range. The carnage continues from there, but Vaughn’s preference for constant motion is plain, swinging the camera not to follow Firth’s face so much as his arm, for it is his arm that holds the gun, wields the knife, uses the lighter. First Class is subtle. Erik finds Shaw. Charles incapacitates him. And Erik uses the same coin that he had been asked to move decades earlier as his instrument of revenge. Vaughn treats this violent moment as the polar opposite of what he’d use in The Secret Service. His camera pans right. Erik moves the coin slowly, and we see that circle through its various stages, as it gets close to Shaw’s forehead, as it enters his forehead, the camera panning across his head, until the coin emerges, bloody, from the back of his head. The superhero – for at this point, Erik is still working as superhero, still acting as part of the X-Men, still fighting to prevent the world from nuclear annihilation, and still building his friendship with Charles – has decided to be executioner. The superhero is already judge and jury. S/He has incredible leeway in the field to track his or her own suspects, as we’ve already covered. The X-Men are not answerable to anyone besides Charles and Erik at this point, and they can fight with Shaw and his crew however they like. But there’s a clear sense for some of these X-Men, most of all Charles, that they are not out to be the executioners. Erik has that in him, and when he does it wearing his X-Men uniform and getting an assist from his fellow X-Men leader to do so.

There’s a corollary to the Dukakis test in Erik’s decision, but with Nazis: “Would you kill the Nazi who killed your mom and several other people if you had the chance to kill him?” It’s a thought we get to have while, presumably, Shaw is having a similar thought as the coin enters his mind. Other superhero movies from this group of twenty-five will pose the question of “kill or don’t,” and we’ll get to them. None of them have a moment like the one in First Class where the violence is slow. Violence in superhero movies is fast. Not The Secret Service fast, but definitely fast. Cap and Bucky face off in The Winter Soldier, Hulk smashing Loki in The Avengers, Cheetah slashing at Wonder Woman in Wonder Woman: Bloodlines. Speed is of the essence. The coin is slow. First Class lets you really savor what that violence is like, the violence which bolds, italicizes, and underlines the purpose of the superhero film. I don’t think First Class blames Erik for being more bloody-minded than Michael Dukakis. But just as the scene is shot in a way that’s unusual, so too is the conclusion that First Class draws about taking the next step from supernatural violence to unnatural death.

Batman 1966

The alternative to killing, naturally, is running around with a giant bomb and trying to figure out where to throw it that won’t blow up nuns or ducks or butane. Batman 1966 is a difficult movie to fit into this genre because it never really embraces violence. I’m not sure there’s a live-action Batman movie that has played more into the “world’s greatest detective” element on Batman 1966. You see some of that in the Long Halloween movies as well as Gotham by Gaslight, but here, the emphasis is on the mystery of the strange substance that can dehydrate an individual and turn them into dust. What’s exceptional about Batman (and Robin) is their ability to make wacky connections, and then to intercept those wacky villains with their wacky vehicles and wacky tech. As I did, one hears about the shark repellent long before one ever sees the movie, and what I did not expect was how rapidly we get to the shark repellent. The shark repellent is not merely a memorable gag, what with Batman hanging on to a rope ladder will trying to spray the very thin shark chomping around his feet. It’s a statement of intent. Batman 1966 understands what the Joker understands: there is something very funny about a guy dressing up in a costume and trying to apprehend criminals.

In the decades since, led by comic books and then exceeded in movies, Batman has become much more threatening, and his augmentations have become pronounced, so pronounced that through his industry, cleverness, and technological know-how, he can bring Superman himself to his knees (The Dark Knight Returns – Part Two, Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice). Batman 1966 is barely trying to contain the Joker, the Riddler, and the Penguin. Whether or not he’s even trying to contain Catwoman is up for debate given the kind of flirtation they have, a flirtation that wears cotton and smells like aftershave. Batman 1966 is a unique superhero movie, a representation of a path that the genre has never been willing to follow wholesale. Even Batman: Return of the Caped Crusaders, the 2016 animated movie which returns Adam West and Burt Ward, doesn’t really want to be as lighthearted as Batman 1966. Most of the movie features an increasingly grumpy Bruce Wayne who scolds Robin and fires Alfred. It’s Catwoman’s fault, but that doesn’t stop the movie from being an unpleasant experience. Batman 1966 puts the caped crusaders in the path of these leering villains just as much as the legacy sequel does. If every choice made in the making of a movie is a crossroads with diverging paths, Batman 1966 always chooses the path of greatest levity. Return of the Caped Crusaders has some absolutely brutal puns (“we’ve been foiled,” Batman says after receiving tinfoil from the Joker), and Catwoman’s insistence on killing Robin made me smile, but in most of its runtime it’s as humorless as Christian Bale or Ben Affleck’s forays into the character.

Vindicated!

Spider-Man 2 is the last of the comic book four-stars I have, and after having gone long about it while I was going longer on why I despised No Way Home, I’ll only go over the broad strokes here. What makes Spider-Man 2 the best comic book superhero movie of them all is a belief in change. The superhero genre does not open itself easily to change. Depowered characters repower themselves (Superman II). The dead speak (Spider-Man: No Way Home, Batman: Under the Red Hood, Justice League, maybe it’s easier to list the ones where no one comes back from the dead). The timeline itself changes (Avengers: Endgame, Justice League Dark: Apokolips War). The Suicide Squad movies get after this idea that there’s always another mission, that you’ll never actually get any time off your sentence. How many times does Superman have to defeat Lex Luthor, Batman the Joker, X-Men the Sentinels? It’s neverending, and it’s neverending on purpose. Spider-Man 2 envisions an ending, and it’s an ending which sees the superhero and the supervillain as finite roles. The superhero can take off the mask and be a precocious geek. Remember the train sequence, “He’s just a kid.” The supervillain can take off the tentacles and remember his life before as a noble figure. They’re not secret identities to be traded on: they’re real identities, and in the face of a sobering and potentially disastrous reality, Otto Octavius regains control. Spider-Man 2 does for the superhero movie what Witness did for the cop movie. What used to be negotiated, in the end, by violence, is negotiated by a dramatic appeal to probity.

Unbreakable

That leaves Unbreakable, which, with apologies to Sam Raimi, is shot as adventurously as any superhero movie ever made. If you head to the Cinemetrics database, you’ll see that the average shot length in Unbreakable is about seventeen seconds long, maybe a little more. (The median shot length is about eight seconds.) Much has been made of this, but that’s wild. That’s an eternity in a superhero movie. The rules of the genre make rapid cuts essential; the mind can only stomach so much of the special effects, practical or CGI, that a superhero movie uses. But an average of seventeen seconds per shot, a median of eight seconds per shot, is gaudy with ambition. Shyamalan has the same median shot length in Unbreakable that Antonioni does in Red Desert, a similar average shot length as Visconti does in Death in Venice. The similarities end there, and harshly. The imagery and camerawork of Death in Venice is sacred, where that of Unbreakable is merely inventive. Long before Zack Snyder got in there with “Superman is literally God,” Shyamalan’s movie tackles the myth of superheroes. In the film, that’s a myth Samuel L. Jackson’s character believes in with a holy fervor, enough to lead him to terrible misdeeds in order to bring a superhero into reality.

The tension in Unbreakable is not a physical one, for the most part. It’s a scheming movie. “Mr. Glass” is a Luthor type, the genius who, in Shyamalan’s story, is not merely unable to meet David Dunn in hand-to-hand combat, but barely able to exist in the world because of how easily his bones break. David, for his part, has two mental concerns to manage. One is the ESP that he’s developed for criminals, a capability that’s first explored in a lengthy stadium sequence. The other is the dilemma of his son, who believes that his father has superheroic abilities and who goes to extraordinary lengths to prove it. In one of those seemingly endless shots, David has to talk Joseph out of shooting him. If you’re a superhero, it won’t hurt you, Joseph’s logic says. Like Gideon, he wants to test the strength of what seems to him a divinity. Unlike the one Gideon tests, his father is not convinced that he can actually survive such a rigorous assessment. In a similar movie, the camera would stay mostly static, with hard cuts between Joseph and David and Audrey, hoping to build tension that way. In Unbreakable, an unthinkable possibility on a personal scale is far more threatening than the unavoidable scourging of Sokovia in Age of Ultron, or the random violence undertaken by the Mutants in The Dark Knight Returns. David Dunn goes on to fight criminals, goes on to hear the monologue of Mr. Glass explaining all. But the darkness to overcome is in his own kitchen, not on the streets of Philadelphia.

The Letterboxd 4.0 Crowd

Here’s every American superhero movie on Letterboxd that’s averaging a rating of 4.0 or better:

- The Dark Knight – 2008, dir. Christopher Nolan

- Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse – 2023, dir. Kemp Powers, Justin K. Thompson, and Joaquim Dos Santos

- Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse – 2018, dir. Bob Persichetti, Peter Ramsey, and Rodney Rothman

- Logan – 2017, dir. James Mangold

- The Incredibles – 2004, dir. Brad Bird

- Batman: Mask of the Phantasm – 1993, dir. Bruce Timm and Eric Radomski

- The Batman – 2022, dir. Matt Reeves

- Avengers: Infinity War – 2018, dir. Joe Russo and Anthony Russo

- Guardians of the Galaxy, Vol. 3 – 2023, dir. James Gunn

- Batman: The Dark Knight Returns – Part 2 – 2013, dir. Jay Oliva

I think it’s nice that there are ten of these.

Infinity War

I went into the Letterboxd reviews for this one, because when I look at Infinity War, I see it as one of the last moving boxes you pack up. You have all this stuff that didn’t make it into other boxes, but this has to come with you to the new place. Some of it might even be important, meaningful stuff that you couldn’t actually put in a box you packed up earlier because you still needed it. This final box is above else full, and full almost at random, impossible to unpack efficiently. There are other people who look at Infinity War and see the Grand Canyon. I’ve screenshotted a couple, but I want to link to this review, which I think speaks to the enthusiasm people feel for this movie, and this other review, which has a fascinating first paragraph and a very, very amusing final one. Anyway, screenshots.

Infinity War is, for a certain kind of viewer, about as big a piece of art as they can imagine. It goes further than just saying that if there’s a lot of something, that’s good. Infinity War is only two and a half hours but it is, of course, the length of every MCU movie that preceded it. It took a long time for this movie to come to fruition, and this feeling that the length of something does something to its quality is not true just for superhero fans. Television critics will tell you that the length of time we spend with the characters and events in a TV show is the backbone of what makes it an important art form. (The comparison between the MCU, from start to Infinity War with Game of Thrones, from start to Red Wedding, is meaningful. A lot of background that was built up into a frenzied moment of potential triumph only for it to end in, it seems, terrible loss. Game of Thrones handled that concept better, clearly, seeing that its treatment of the Red Wedding wasn’t “Just kidding!” On the other hand, I think it’s fair to say that both franchises never really recovered. People get impatient having to wait for something that built up again, but at the same time they really want to have that moment built up again for them, just…faster. It didn’t work for Game of Thrones either.) Even movie critics soften up a little bit when they watch something three hours or more. They get a little nervous about saying they burned their time on something which wasn’t very good, or they fall into the same trap of believing that because it was long it was good. It’s boring to say that Infinity War is primarily interesting as a cultural product and not as a film. Even the people who adore the movie tend to tacitly agree. Yet what does one say about it as a movie? I’ve seen enough commercials where you line up all the Happy Meal toys together to understand that longing for acquisition and completion.

The Newcomers

If we check back in a couple years, I’d be surprised to see The Batman and Vol. 3 with this group. Anything as recent as those two movies gets a little bump on any movie ratings site, and as time goes on, star ratings fade. I also think both of those movies might be getting some help compared to the recent companions they have in their business models. The Batman has nothing to do with the DCEU brand that’s generally been making bad movies and which has the PR problem of “they’ve been making bad movies and we’re not pretending otherwise.” Robert Pattinson’s dreary, mysterious take on Bruce Wayne/Batman is worlds away from Ben Affleck’s, who probably has more in common with Adam West than he does any of his other predecessors. Vol. 3 is a Phase Five entry in the MCU, and if you’re inclined towards this movie and not Quantumania or The Marvels, then presumably this feels like a return to form. There’s no multiverse in here. It’s the same characters from the previous two Guardians movies (and everywhere else they’ve been), with emphasis on the story of Rocket’s past rather than Rocket’s gazillion futures. Both The Batman and Vol. 3 scratch itches that fans desperately needed scratched. There’s interesting stuff happening in The Batman, especially since it looks at Thomas and Martha Wayne as individuals who existed and did things before they were murdered. Vol. 3 is dry business, acting like George Lucas’s quote about strangling a kitten for audience sympathy was good advice as opposed to condescension. In any event, we’ll see if they’re still up here, or if they’ll join movies like Batman: Under the Red Hood, Spider-Man 2, and Avengers: Endgame as 3.9s.

Animated Batman

On the other hand, we have two older animated Batman movies which have stood the test of time for Letterboxd raters. Mask of the Phantasm is, to use a technical phrase, old as hell in comparison to most other films in this genre. I’m going to let Gene Siskel explain what he liked about it so much:

Siskel has his eye on the right things here (he and Ebert agree that animation for adults is ripe for emergence), and the look of Mask of the Phantasm is tops on his list. There have been so, so many Batman animated movies done so, so many ways in the thirty years since this movie was released, but you could make a strong argument that the art here is better than it is any of the others. Mask of the Phantasm has the all-important silhouette of Batman down to pure geometry: the shape of the cowl atop a trapezoid. That’s Batman. This is a movie where everything is “done the right way,” a good-looking movie with a clearly defined style, absolutely professional voice acting, a story which is a little bit twisty but never convoluted. Nor does the film shy away from some of the questions about vigilantism that ought to inflect any Batman movie. The Phantasm is taking the war to Gotham’s crime lords, shedding blood, and ending their misdeeds for good. Batman sheds much less blood and can only hope to interrupt their crimes. Characters in the film blame Batman for what the Phantasm is, in truth, doing, and they believe that it might be Batman who kills because he has already gone so far outside the law. The weight of history is light on the shoulders of Mask of the Phantasm, and by wearing that history lightly, the film might be the most consistently satisfying Batman movie of them all. The Joker is furikake for a dish that needs someone to wear light purple, to have a white face when everyone else’s is shrouded in black. The Joker works as seasoning at least as well as he works as a featured dish, and Mask of the Phantasm uses him to supplement a villain who is unique in Batman movies. The substance is more than adequate, but like Gene Siskel tells us, the style is what makes Mask of the Phantasm good.

Whatever Mask of the Phantasm is, The Dark Knight Returns – Part Two is not. Mask of the Phantasm is not cheerful, precisely, but there’s a deftness in its steps, an appreciation of the genre’s capacity for enjoyable stories. Part Two is a plodding movie, alas, one that feels the weight of the graphic novel’s importance and which never really manages to translate that into a good movie. It’s a pity, because Part One belongs in the top ten percent of superhero movies made in this country. Both parts of The Dark Knight Returns cotton to the silly conservatism of the original graphic novel, which treats characters as sock puppets who artlessly set up an unfunny punchline. This is what The Dark Knight Returns has in common with The West Wing. In Part One, these eye-rolling moments fade into the background of a troubled mood. How frustrated and dim Part One is, how appropriate it is that Batman’s primary foes are, for all of their posturing, mere street hoods. Gotham is overrun, not overlorded. Although none of Batman, Frank Miller, or Jay Oliva seems to appreciate that decapitating the head of a terrorist organization tends to make the terrorists proliferate rather than dissipate, there’s a satisfying arc in the film, an appreciation of the limits of Batman, the reliance of Batman on others, as well as his strengths, the way that he inspires people to rely on him.

Part Two is little more than Bat-propaganda, which even by the standards of Bat-propaganda lays it on a little thick. In a future post, I’ll have a lot more to say about Jay Oliva, the director of both parts and the most important director of superhero movies. Suffice it to say that Part One appreciates a fact of the genre, and Part Two devolves into accidental genre parody. In Part One, we get to watch Batman beat the shit out of people. That is, in no small part, the point of the superhero genre. In Part Two, Batman gets into a final fight with the Joker and has a kryptonite-infused team-up against the Man of Steel. Both are forced affairs, to say the least. The Joker comes out of his catatonic state and wreaks havoc with hypnotic lipstick, which, in terms of the grit that this universe works within, is as worthy of eyerolls as Bartholomew Wolper. Superman is ordered to neutralize Batman because he’s making Ronald Reagan look bad in the wake of nuclear holocaust, and so the two of them have a very loud fight where both wink at each other at its conclusion. Part Two sermonizes until it’s blue in the face, which is personally offputting, but then again, people still like going to church.

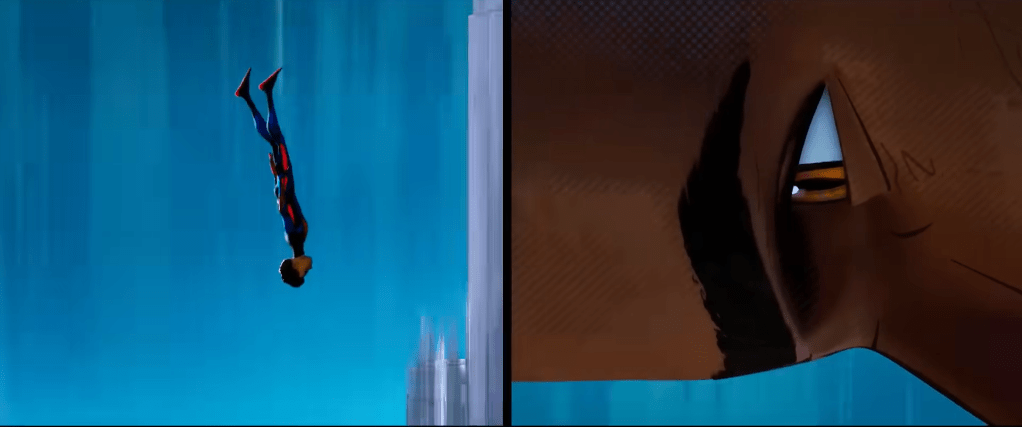

The Spider-Verse

The animation styles of the Spider-Verse movies are dictated by Chris Miller and, more vocally and problematically, by Phil Lord, two of the producers and writers on those pictures. The Lord and Miller style, which was introduced to the superhero genre with The LEGO Movie, favors the dense frame, loading each cel with an astonishing amount of detail. Where the big screen tends to call attention to the rush-job VFX of your MCU tentpole, the big screen is the ally of the Spider-Verse films. It allows you to see just how much is going on, lets you marvel at the sheer amount of information you get, and because the style is fluid (the watercolor effects of Gwen’s backstory in Across the Spider-Verse against the choppy, geometrical finale of Into the Spider-Verse), the results can be hypnotic. It’s an animation style which breeds FOMO while you are in the theater watching it; you’re sure that you are missing something that’s been painstakingly included and it hurts a little to know you’re missing it. It’s the style which best suits the multiverse, which is its own kind of FOMO; there are so many versions of the story that you’ll never see, and so many items in the frame to rack up as you piece together the version which stands before you.

What goes without saying, perhaps, is that the insistence on dense frames is something which only stands out compared to other superhero movies, which cannot afford to make their backdrops anything more than brown or black in order to make the job of underpaid visual effects artists easier. The generally quoted number of bubbles hand-drawn into The Little Mermaid is over a million, and even if that’s off by 25%, that’s still an enormous amount of density built into each cel which is not meant to attract our attention but enhance our immersion. And when we talk about dense frames outside the superhero genre, something like what we’d find in Max Ophuls or Orson Welles, then it’s not really a question of comparison so much as it is the question of a beatdown.

The Spider-Verse movies do a lot of things right. Miles Morales is a real teenager, and like many teenagers, he is precipitate, impetuous, joyful, and idealistic. Interpreting Spider-Man through him gets at what all of us suspect about being a superhero. When you’re not saving the world, having superpowers must be fun. Not just fun in an Instagrammable way, like when Tony Stark takes his order from Randy’s Donuts to the roof. It’s fun like play. Much has been made of the wish to fly and how characters like Superman fulfill that. I’m not sure that what Spider-Man does, web-swinging between buildings and incorporating the belly-dropping of a roller coaster with each lunge, isn’t a lot more fun. Animation captures this feeling better than live-action with CGI, I think. Even beyond the association we have between animation and childhood, there’s an ease in the motion of animation that simply works better than whatever we have to fudge through with special effects alone. More than your average Peter Parker, who just has Aunt May in his life, teenage Miles is explicitly responsible to two parents who are very hands-on. The irony of Spider-Man is that despite his status as vigilante, completely unanswerable to all authority, the boy is hilariously answerable to all manner of normal people. That’s even more ironic in the case of Miles Morales, whose father is a cop. It’s also been fun to see Spider-Man pitted against villains who have been absent from his movies before, like Kingpin and Spot. The voice casting has been great across two movies as well; Shameik Moore and Hailee Steinfeld are both winners. The first Spider-Verse restored likability to a genre that was in dire need of it. The second one proved that if you make something likable in this genre, someone will come along to give a terminal case of bloat.

Heroic “Realism” – The Dark Knight and Logan

These are the Washington and Lincoln of superhero movies; we just talked about Jefferson and Teddy Roosevelt. Both of them present the superhero in something that’s meant to resemble a real, grisly kind of world. Both of them present the superhero as a figure who is probably doomed. Both of them are nervous about the idea of other superheroes even existing. We’re going to get to both of these in a minute in more detail.

The Dark Knight, Logan, and Black Panther

Last time out, I wondered about if there could be a superhero movie that came up to the level of The Godfather, redefining its genre the way The Godfather redefined the gangster movie, inspiring imitators and leaving a permanent impression, expanding what is possible within the genre. The Godfather of the superhero movie, conveniently enough, would be able to produce a sequel just as rich and complex as the original; perhaps, in the eyes of some critics, it would be even better. The superhero Godfather would be a no doubt about it five-star movie, a Best Picture winner, a Sight and Sound top 100 vote-getter.

As fun as it would be to go through every superhero movie ever made and then say why it isn’t the superhero Godfather, that’s a marathon and I’m out of shape. I want to start this off by explaining why the movie I’m looking for is not The Dark Knight, Logan, or Black Panther.. Obviously they’re not my choices for the best superhero movies, and as Letterboxd would tell you, they’re not necessarily that app’s favorite choices either. These are the movies where, when we talk about superhero movies of this century, we generally conceive of the genre as having taken a step forward.

It’s not The Dark Knight. I know. It’s IMDb’s third-ranked movie of all time. It is twenty-first on Letterboxd. Heath Ledger won an Oscar for his performance in the movie, and it doesn’t hurt for the film’s credibility that Christopher Nolan has since won Best Director. It made so much money, which, when we talk about The Godfather, is a pretty important consideration. It is the common benchmark of superhero movie quality. But I want to show you something.

This is the twenty-sixth page of the most recent They Shoot Pictures, Don’t They? Top 1,000. TSPDT is utterly comprehensive, using thousands of data points, not simply from lay viewers but from people with critical backgrounds. There is no resource that I trust more to lay out which movies rate “higher” or “lower.” In my last post, I used the most recent Sight and Sound ballots to make this point, but since I published that one, TSPDT has updated, and I think this makes two very important points. Firstly. The Dark Knight is ranked as their 643rd best movie, based on all of the mountains of information they use, out of a starting list of more than 25,000 movies. That puts The Dark Knight in the top 2.5% of their data set. That’s a phenomenal accomplishment. Look at the movies around it: Rebecca, Frankenstein, fellow Letterboxd favorite Harakiri. From the perspective of scale, it’s amazing that The Dark Knight is received so favorably. Secondly. The Godfather is sixth, Part II is thirty-third, and Part III is 999th. Critically speaking, The Dark Knight is closer to Part III than it is either of the first two Godfather movies.

This is the part where I think it’s almost fair to yell at me and say something along the lines of, Well, what do you expect? Are you seriously waiting for a superhero movie that we can look at as one of the ten best, fifty best movies ever made? And the answer is…yeah, kind of! The point of this exercise is not to say “When are we going to get a really good superhero movie?” but “When are we going to get one of the greatest movies ever made?” When are we going to get a superhero movie that isn’t rated lower than nine of Ingmar Bergman’s movies, or eight of Jean Renoir’s? If there’s one thing that we can take away from A Personal Journey with Martin Scorsese Through American Movies as it pertains to superhero movies, it’s that greatness is a possibility within any genre. There’s no such thing as “oh, it’s just a western,” or “it’s just a gangster movie.” The point of this thought exercise is to find, and if not to find then to imagine, a movie that we don’t merely say, “It’s the best superhero movie,” or “It’s great for a superhero movie, but…” The Dark Knight is clearly falling short on that front. It was received with tremendous acclaim in the moment, and it has only garnered more in the intervening years. It changed the Academy Awards, which had run with five Best Picture nominees since the 1940s, and which chose to expand the Best Picture pool because people were so incensed about the lack of a nomination for The Dark Knight. What I don’t expect, and what I don’t think I have reason to expect, is that this movie will climb another 550 spots in the next twenty years. Sure, it’ll become more entrenched in the canon, but I think it will be entrenched like a layer of stone in a canyon, which may only rise because of spectacular erosion.

Even if none of that hits home because you’re of the mind that The Dark Knight is about as good as The Godfather, there are other reasons to believe that we aren’t looking at the newly risen apex of the superhero movie. Part of the greatness of The Godfather is in its reach. Richard Brody argues that American prestige cinema was faced with a choice between the raw emotional intimacy of John Cassavetes and the grand metonymic scope of Francis Ford Coppola in the late ’60s and early ’70s, and then went on to choose Coppola. As we all know, 2008 is the year of Iron Man and The Dark Knight, and as we all know, superhero movies chose Iron Man as the model to follow. Digital effects were chosen over practical effects. A hero whose irreverence disappears into duty was chosen over a villain whose ideological imprint was unmistakable. A film which actively invited speculation about its many sequels was chosen over a film that would have worked well without one. The world picked Marvel’s interpretation over DC’s. DC didn’t even pick Nolan’s interpretation of the world. They picked Zack Snyder’s, even when Zack Snyder was being erased from Justice League.

If it were The Godfather of superhero movies, the influence of The Dark Knight would be felt more heavily within the genre itself, to say nothing of the influence it would have had on prestige filmmaking more generally. The offshoot with the shortest path to The Dark Knight is probably Joker. But Joker, as literally every critic on the planet had to tell you, was stylistically influenced by Mean Streets and Taxi Driver and The King of Comedy. Joker is a character piece about Arthur Fleck, which would be a development in the superhero genre if Joker were a superhero movie. The Dark Knight is a landmark for Nolan, and a landmark for superhero movies, but I really can’t see a way that we could call raise it up as especially influential. (Christopher Nolan might be the John Shelby Spong of superhero movies. It’s interesting to take the superpowers out of it in the same way it’s interesting to take divinity out of Christianity, but it’s hard to imagine the concept catching on a big way.) Fatherhood has been at the center of superhero movie anxieties. The end of the world has been at the center of superhero movie anxieties. Neither of those concerns are seriously approached in The Dark Knight. Outside of comic book movies it gets even harder to identify the downstream effects of The Dark Knight. Is Zero Dark Thirty as close as it gets? Sicario? It’s certainly not a revolution. The Dark Knight is not easily followed. All you have to do to see that is to remember the responses to The Dark Knight Rises, which took some flak at its release for not being the tidal wave that The Dark Knight was.

It’s not Logan. Logan predates Hereditary by a year, and I think the reason I’m not that impressed with Logan is the same reason I’m not that impressed with Hereditary. Hereditary is kind of a horror movie, but it’s mostly a character study about terrible family grief. It’s Woody Allen with a couple jumps. Logan is kind of a superhero movie, but it’s mostly a character study about a dying man trying to leave a just legacy. It predates News of the World, but that’s probably the non-superhero movie it has the clearest surface relationship to. The thing about The Godfather is that it’s not kind of a gangster movie finding the American rot which poisons the immigrant experience. It is, very much, a gangster movie. The film is spectacularly violent. It looks at Bonnie and Clyde breaking the glass ceiling of armed execution five years earlier and says, “Anything you can do I can do better.” It also opens the door and stares down the attic wife of the American dream, but it does that by embracing the character of the gangster film, not by running from it. I don’t think it’s right to say that Logan is embarrassed of its superhero origins. Even if the X-Men are functionally gone, the movie is too reliant on the past characterizations of Professor X and Wolverine, too connected to the iconography of the movies predating it by fifteen years and more. But at the same time I don’t think it’s all that interested in them. Logan wants to take its inspiration from western travelogues. It wants to be True Grit where Mattie is more of a prop than a character. It wants to be The Searchers where you can just like the grizzled, past-his-prime warrior. Influence weighs heavily on Logan, which can get as dusty as any western, but which doesn’t really want to confront the ideas of its own genre. The X that marks Logan’s final resting place is a reminder of which boardroom this movie’s grandfather was born in, not a statement of where it’s wanted to lead us.

It’s not Black Panther. Even more than The Dark Knight, Black Panther probably has the best critical reputation of any superhero movie. Go on Metacritic and it only has positive reviews. Go on Rotten Tomatoes and it has a single negative review from a top critic. Matthew Lickona of the San Diego Reader comes down on the side of “not great,” not even getting to the point of a pan. His kicker is the thing that really sticks with me: “Ultimately, it’s more interesting to think about than it is to watch.” I disagree with a lot of Lickona’s review. I don’t think Black Panther has a pacing problem, and I think carping about physics in a superhero movie is a little bit precious. But the last sentence is the problem with Black Panther. There’s a lot in the film which, if you summarize it, sounds like we’re doing something fascinating.

No Marvel movie, perhaps no superhero movie, has ever been able to credibly carry so many buzzwords. Afrocentrism (Kenneth Turan), cultural movement (Robert Daniels), Black liberation (Manohla Dargis), of-the-moment (Roxana Hadidi), personal (Michael Phillips), epic (Joe Morganstern), geopolitical (Sandra Hall), Shakespearean (Kevin Maher). But the question remains. Are those ideas like tags on a blog post, or are they genuinely built into a great movie? Like, an epic African fantasy created in opposition to a Eurocentric gaze where a son is placed in conflict with his father? Is Black Panther as good as Souleymane Cisse’s Yeelen? Does Black Panther really approach Yeelen in quality, in its approach to myth, in powerful images in a final showdown? To me there’s not much of a comparison. Yeelen is much the superior work of art, superior to Black Panther in virtually all phases, but more than that, it ties in its intellectual ideas faithfully with its images. Ryan Coogler manages to pay lip service to ideas like Black liberation and postcolonialism, but if you can confuse him for Med Hondo, then you need a stronger prescription. Perhaps they share similar feelings; it could be that Coogler is even more passionate than Hondo. But Coogler couldn’t have made West Indies or Soleil O if his life depended on it, and Hondo would have found a way to make Black Panther a significantly more penetrating story.

The nail in the coffin of the Black Panther candidacy is in Leonard Maltin’s review of the film, which begins by saying that “Marvel’s Black Panther is, culturally and commercially, the right film at the right time,” and closes by saying, “Any reservations I have will, and possibly should, fall by the wayside.” This isn’t a review. It’s not a statement about art. This has nothing to do with genre. It’s about a limp gesture. It could be true that Black Panther was the right film at the right time, but I can think of no fainter praise. If it can be right for the right time, then it will be the wrong film for another time. No one would condemn Yeelen or West Indies that way. The answer we’re searching for should not be, “Does this movie do Afrocentrism about as well as we can imagine a Disney movie doing it?” It should be, “What is spectacular about this movie’s treatment of Afrocentrism?” full stop.

Can There Be a Godfather of Superhero Movies?

Yes. I believe that it is possible to make a superhero movie that is of commensurate quality with The Godfather. I do not believe that that film exists yet, but just because it does not exist yet, and just because there are movies which have failed to reach that height, does not mean that it cannot exist. In fact, I think there are even lessons to learn from each of these misses about what might create the great superhero movie.

The great superhero movie will need the intensity of the performances from The Dark Knight. I think it’s hard for a really great genre movie to perform the wink of irony about itself, or about its genre. There’s a gentle teasing of old Hollywood in Singin’ in the Rain, but there’s nothing ironic about Gene Kelly or Donald O’Connor dancing. The romance subplot of The Searchers is good for some laughs about the easily wounded pride of frontier folk, but there’s nothing ironic about John Wayne raising his rifle against Natalie Wood. The great gangster movies are all about irony, the funhouse mirror image of the American Dream, the hubris of people who think they’ll always stay on top of the world even though there’s so much evidence to the contrary. There’s nothing ironic about the way Joe Pesci acts in Goodfellas or The Irishman.

I think this is why the end of the world is so often on the minds of those who make superhero movies. The superhero wasn’t pulled from the serious pages, after all, and the supercharged bigness of superheroes makes them easy objects to make fun of. They’re tempting targets for the comedians who have become more prevalent auteurs in the genre. Taika Waititi, who transformed Thor from Kenneth Branagh’s backslapping Aryan god to a meme machine, has probably had the most success of anyone working in this vein, although one has to mention James Gunn’s very knowing slo-mo shots of the Guardians of the Galaxy as well. If the world isn’t ending, then we start to wonder why it is that Superman wears his underwear on the outside. If the world is ending, then the superhero is less funny. No matter how much we’ve chortled at them before, we have to hold back our laughter as s/he becomes the only person who can stand in the way of total disaster.

The Dark Knight is not about the world ending. The Dark Knight is about a criminal who masterminds his way into becoming the chief crimelord of a vulnerable city. The stakes on this one, compared even to your average MCU joint, are pretty low. But people love The Dark Knight, I think, because the movie elevates those fairly low stakes while also treating the results of the Joker’s spree like they’ll prove the existence of morality itself. No one thinks that’s funny. Even the Joker doesn’t think that’s funny. Heath Ledger, Christian Bale, Aaron Eckhart, Michael Caine, and Gary Oldman are all acting to the brim in this movie. Each of them is selling the idea that Batman represents a form of outward-facing moral logic, and that the Joker represents an immoral chaos, and that the victory of the latter might forever erase the goodness of the former. I don’t think it’s even the look of this movie that brings this about. It’s in the monologues that Bale and Ledger rasp and wheedle their ways through. It’s in the way Eckhart and Oldman strain their facial muscles and make their eyes bulge. The Godfather of superhero movies is going to have to treat the superhero and the supervillain and their supporting casts with this kind of seriousness.

The great superhero movie will need the attention to finality of Logan. It will have to believe that characters can die and that stories can end. Blame superhero comics, I suppose, but it’s been bred into us that virtually any character can be brought back to life in one way or another. There are multiple film interpretations of the “Death of Superman” storyline. It’s bad business to kill off someone who has already proven to be popular, and superhero movies are, if anything, even more risk-averse than superhero comics. In a violent story, we must believe it is possible for our hero, or our villain, to have died. We have to believe that the game can be played for keeps. Avengers: Endgame is a towering mistake. It has calcified two ideas into superhero movies that I’m not sure we’ll ever be able to steer away from. First, the idea that events that have happened can be altered. Second, the idea that when those events are remedied, things basically go back to normal. There have been multiple little gestures in the movies about the people who are unsnapped and return to their lives after five years have passed without them. In a good movie, this would be an issue that we’d see discussed rather than merely remarked upon, lived in as opposed to pointed at. The MCU was never more like little boys playing with action figures when it rolled its eyes at everyone returning from the Snap. To the credit of Logan, and the credit of the people who made it, the film treats each action, each disappearance, each death like it’s permanent. No one’s going to do something goofy to ensure that the Reavers are defeated in such a precise fashion that it creates the least collateral damage. What happens is untouchable in Logan, and when it does feel like it approaches the status of character study, it’s because of that quality. Logan is not as super as I think he needs to be to make Logan a great superhero movie, but the story is grounded in temporality.

The great superhero movie will need the political curiosity of Black Panther. When I said earlier that I felt that the film never does more than gesture in the direction of its buzzwords, what I mean is that it does not credibly structure itself to approach the possibilities Killmonger works toward. There’s never a time when we really believe that Killmonger might successfully point the gun at the colonizers and hegemons of the world because the movie isn’t put together that way. It’s built on the idea that the hero must lose to the villain in physical combat in a mid-movie sequence, and then the hero must defeat the villain in the rematch at the end of the movie. It is obviously very interesting that Black Panther is talking about political isolationism and mentioning the effects of the Atlantic slave trade, but the movie itself is not all that interested in exploring the effects of those things. Wakanda is closed until it becomes open. We see that there are some plans T’Challa has in mind for what that will mean, but the movie doesn’t get to explore those. No movie gets to explore those. Black Panther is curious but does not really believe in change. That’s not unusual. No superhero movie really believes in change. It’s rare enough that Black Panther has something in common with Watchmen or The Dark Knight Returns movies or The Incredibles, this idea that the superhero is not a tacitly political figure but an expressly political one. The successor to Black Panther will have to reckon with real political change managed earnestly and executed honestly.

[…] The first part of this series, where I talk about the historical context for superhero movies as a genre, is here. The second part, where I talk the superhero movies I think are the best, as well as the superhero movies other people think are the best, is here. […]