Recently, I was inspired by the unveiling of the Variety list of the 100 best horror movies. I was curious why the list had been received with trepidation. To sum up the post, my conclusion was that Variety included a number of older movies which rely more on atmosphere than gore or jump scares, and that in making that choice, the list peeved people who were expecting more recent, “scarier” entries. I think I made some decent points about the Variety list in that post, but it felt a little small in scale to me almost as soon as I published it. So I went spelunking for more top 100 lists, and found five more. I was already using the Fangoria readers’ list and the Time Out top 100. I’ve since added top 100 lists from Collider, IGN, Indiewire, Paste, and Rolling Stone. It’s still not a huge sample, but I feel better about working from these seven critics’ list and one readers’ list than I felt working from three total.

The Basics

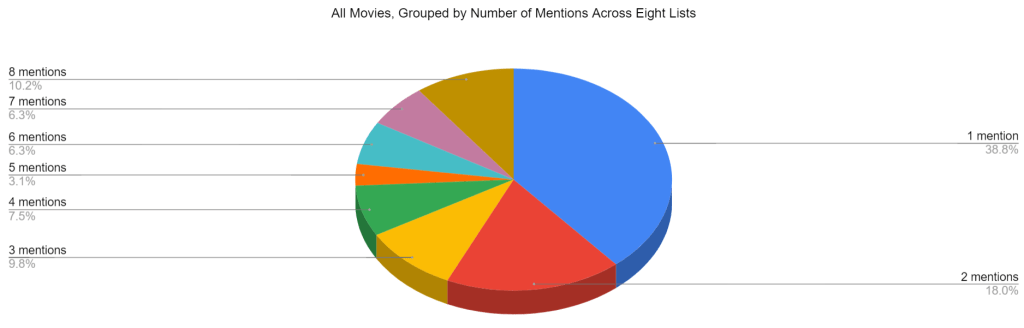

If you don’t count The Abominable Dr. Phibes popping in at #101 on the Rolling Stone list (sorry, Kumail), we have 800 potential movies to work from. It’s unrealistic to expect 800 different movies, obviously, and it’s probably unrealistic to expect even 350 different movies. In total, there are 255 movies listed at least once across all eight lists. 154 of them are named on at least two lists.

My initial thought after looking through the data and coming up with this chart was that this seems low, somehow. We’ll talk about how there are some movies that everyone is going to include on their list, and that makes sense to me. All the same, I can’t shake this feeling that everyone copied off of each other, or Wikipedia, or ChatGPT, or something. There’s a broad swath of critics represented in these eight lists, and each publication has their own stable. The problem isn’t that David Ehrlich or A.A. Dowd have finagled their way into writing for all of them. And the problem isn’t that these lists are outdated, or come from totally different years. The vast majority of them have actually been published in the last couple months, and recent releases like I Saw the TV Glow and The Substance are already peeking through. The most common type of movie across these lists are movies mentioned once. Then movies mentioned twice. And then movies mentioned eight times. What I want to understand is why everyone seems to think the same way, and why the fans, relatively speaking, are on their own island.

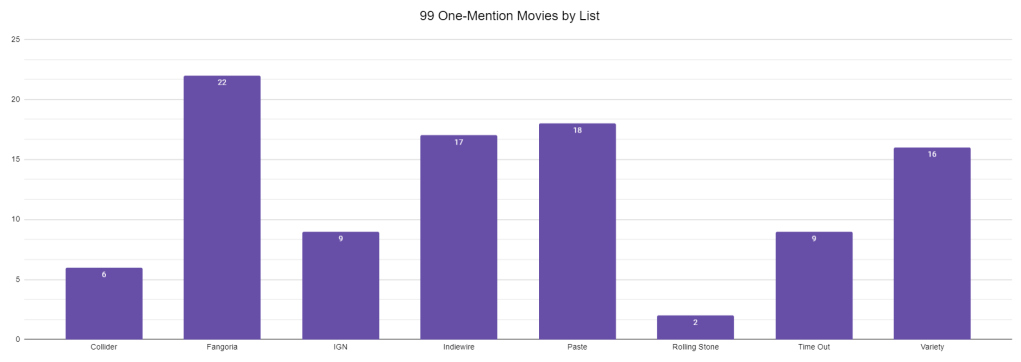

I love that there are ninety-nine movies mentioned once across the eight lists. They make their own top one hundred (sort of, maybe I should be paging Dr. Phibes), one that isn’t polluted by groupthink or decency, but relies on individual tastes and plugs from critics. You can tell which lists are most creative, most free by how many movies they include which are only named on that list. A lot of the movies named just once are smaller films made for cheap, potential Blair Witch Project movies that just never blew up the same way: The Invitation, Kill List, The Loved Ones, Session 9, You’re Next. You can feel each list trying to plant a flag with movies like these, for no genre so consistently rewards the cost-effective entry as horror. For those of us who aren’t trawling streaming services for the most recent horror movies, or for those of us who can’t go to festivals, this is where the lists can be most educational, which is typically where top 100 lists are at their best.

There are some movies from this list of ninety-nine that I’m a little amazed only show up the one time. When I was old enough to know non-Disney movies existed, Saw was the horror movie most breathlessly feted by the kids I knew. Yet only Fangoria includes Saw. I thought Gremlins was a much more popular title than this (the first time I used Letterboxd on my phone after midnight I jumped) but only Variety had a place for it. Only Indiewire sprung for a number of titles which I think of as especially great horror movies: Perfect Blue, Tetsuo: The Iron Man, and especially Antichrist. I’m less sure that Altered States is a horror movie than Indiewire is, but if it is, then it ought to be on more lists. And I’ll make room here for a personal favorite as well. Halloween III is on two lists, but the lovely Nightmare on Elm Street 3 couldn’t bust onto a second one. It’s picks like these that make the one-mention movies a tantalizing group.

These are the lists by how many unique films they include. And…wyd Collider and Rolling Stone. Rolling Stone does this hilariously. They put Island of Lost Souls, the 1932 Dr. Moreau film, at #47. This is an inspired choice. And then they have the French pregnancy slasher Inside listed at #6, just completely going off the board when everyone else’s top tens are practically identical. Collider, on the other hand, has a less interesting slate than Rolling Stone: they uncancel Cannibal Holocaust, include Let Me In as well as Let the Right One In, subject us to What We Do in the Shadows. Time Out doesn’t go off-book that often either. They’re the only people who jumped for A Quiet Place, and I liked that they included The Mist and Pulse when no one else did. Nor does IGN deviate much, although when they do, it’s with buckshot: Scanners, the Zack Snyder Dawn of the Dead, The Dead Zone. Variety, Indiewire, and Paste all try to develop their own personalities, all befitting the publication. And standing alone, after all this, is the Fangoria list. It was filled with unique choices when we were only working from three lists, and now even now that we’ve added five more, it’s still more than 20% unique.

The Critics, the Fans, and a Scary Hypothesis

It’s not exactly insightful analysis to say “fans of a type of movie see the genre differently than critics do,” but what stands out is just how often the critics unite around the same movies.

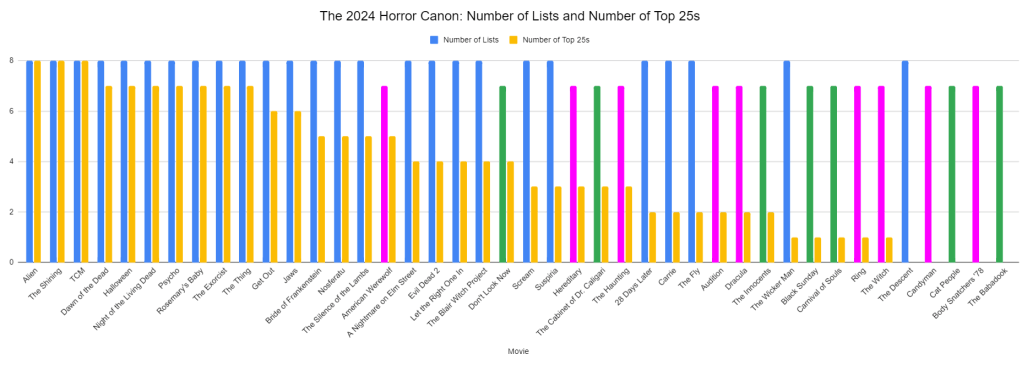

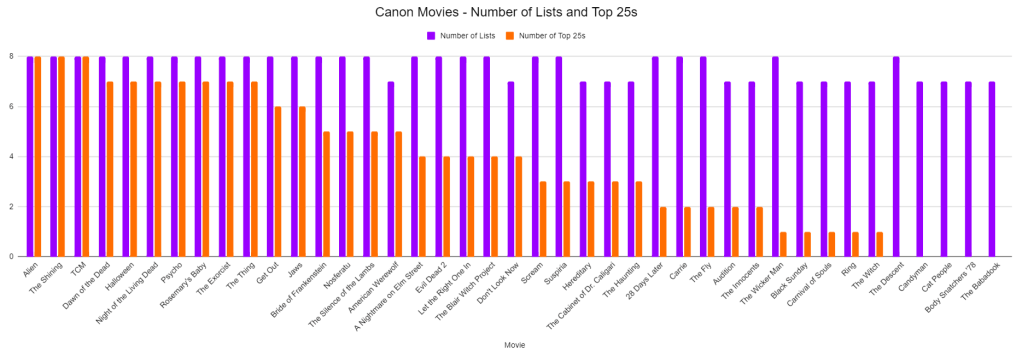

This chart lists every film that’s on seven or eight of the lists I pulled from. I’ve also sorted for how many times each movie shows up in the top 25 of a list. As you can see, there are twenty-six movies named on eight lists and sixteen on seven. Nine (in pink) of those sixteen appear on all critics’ lists but one. For example, An American Werewolf in London didn’t make the cut for Variety. The other seven (in green) don’t appear on the Fangoria list. Even when it’s not unanimous, the critics are overwhelmingly in step with each other.

| Missing from a Critics’ List | Missing from Fangoria List |

| An American Werewolf in London (Variety) | Don’t Look Now |

| Hereditary / (IGN) | The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari |

| The Haunting / (IGN) | The Innocents |

| Audition / (Paste) | Black Sunday |

| Dracula / (Indiewire) | Carnival of Souls |

| Ring / (Paste) | Cat People |

| The Witch / (Indiewire) | The Babadook |

| Candyman / (Paste) | |

| Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978) / (Collider) |

The average critics’ movie that doesn’t appear on the Fangoria list was released in 1962. The average Fangoria movie that misses a critics’ list is from 1986, which doesn’t sound all that recent, but when you consider that the average Fangoria movie was released in 1989, it makes more sense. Again, recency bias is part of what separates our fan list from the critics’ lists, and to my mind it is the one of the essential roles of the critic to supply context that a regular moviegoer may miss. Fluency and comfort with movies going back more than a century is, to me, the crown jewel of that context.

The one movie made after 1973 that’s on seven lists but missing Fangoria is The Babadook, and here’s where I’d like to make a hugely inflated claim based on a single movie out of 255. The Fangoria list is aggressively Anglophone, so we’re missing some popular giallo, some New French Extremity, some Guillermo del Toro you can find on multiple other lists. But the Fangoria list is in large part defined by its avoidance of “elevated” horror. The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and Don’t Look Now are textbook arthouse. Fangoria foregrounds meat and potatoes horror: the paranormal, slashers, zombies. Here’s an article from Vanity Fair about elevated horror from 2019. It tries to get away from the traditional definition of “elevated horror,” which basically always meant “horror movies you’re allowed to think are good that have at least one metaphor” but what it turns into is a defense of “elevated horror” basically meaning “horror movies you’re allowed to think are good that have at least one metaphor.” The usual suspects pop up: Get Out, The Witch, Hereditary and Midsommar. All of those are on the Fangoria list. But Laura Bradley invokes The Babadook as well. (“Is The Babadook not a direct spiritual descendant of Rosemary’s Baby?” Laura Bradley asks. One might reply, “Did you see a different Rosemary’s Baby than the rest of us?”)

I don’t think the absence of The Babadook on the Fangoria list has to do with a female main character. Shoot, not that being a horror fan makes you a feminist, but if there’s one set of genre fans I’d wager on being able to recognize a female protagonist as valuable, it’s horror fans. Nor do I think that they’re shying away from a horror movie about parenting. Parenting is at the heart of The Exorcist, A Nightmare on Elm Street, The Shining, Hereditary, Friday the 13th, Poltergeist, and the somewhat-miscast-as-horror Aliens, all of which are in the Fangoria top forty. I think it’s because the metaphors of The Babadook are so oppressive, so obvious, so overwhelming that the movie is more stressful than frightening. Obviously people can disagree about what’s scary, and as a rule we should believe people when they say a movie has frightened them. I follow a number of critics on Letterboxd who are Babadook partisans. (Alas that the movie came out before Letterboxd took off, meaning that a number of them have rated it but not left a review.) Apparently William Friedkin thought the movie was great, which doesn’t make me feel so good about pronouncing that the film is primarily stressful. The Babadook strikes me primarily as a parable about grief, and that structure is so much of what made the elevated horror era work for critics. It’s not especially jumpy or gory, which is the kind of stuff that works for the Fangoria readers. The end result is that The Babadook is a canonical horror film, as of 2024, despite the fact that the lay horror aficionado seems to prefer Barbarian or Evil Dead Rise.

All of this fretting about what fans think is uncharacteristic for me. The Sight and Sound top 250 is a guiding light for movie lovers. The IMDb top 250 is frivolity, perhaps even risible frivolity. Judging a film’s quality by its box office is silly, too. No one would, in good faith, denigrate the work of Franz Kafka or Emily Dickinson because they didn’t make any money off their literature. What I worry about, looking at these critics’ lists, seeing that they’ve chosen 233 individual movies out of as many as 700, is that they may not have enough context to really differentiate them from the fans. Maybe all these lists are are cursory swipes at the material. The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari has escaped the Portlandia sketch and made all seven of the critics’ lists. Indiewire ranks it as the fourth-best horror movie of all time. So I wonder how it is that none of the critics’ lists referenced The Golem: How He Came into the World. It’s a film at least as good as The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. It’s German from 1920, the same as Dr. Caligari. You don’t get Frankenstein’s monster without the Golem. The cynical response, which I have no basis for but cannot shake, is that critics know they’re supposed to seek out Dr. Caligari but don’t know they’re supposed to seek out The Golem.

What about The Uninvited, the 1944 Lewis Allen movie which uses eerie suggestion nearly as well as 1942’s Cat People? There’s no sign of it on the critics’ lists. You can find Kwaidan and Onibaba on multiple critics’ lists, suggesting their familiarity with Japanese horror of the 1960s. But no one has any space for Kuroneko, the ghost movie by Onibaba‘s director, Kaneto Shindo? I don’t know that I really think of Ken Russell’s The Devils as a horror movie, but let’s grant that it is. Surely if that’s a horror movie, then so too is Mother Joan of the Angels, an austere and much more haunting telling of the same plot. But then again, Mother Joan is Polish and not nearly as salacious. A woman losing her mind in a new, unfamiliar place counts as a horror movie for The Innocents, but no one seems to have space for the very good Let’s Scare Jessica to Death. We like a Canadian holiday slasher well enough when it’s Black Christmas (five lists), but there’s not some huge gap in quality between Black Christmas and My Bloody Valentine. None of those movies place on the Fangoria list either, but that’s just the thing. Fangoria is an Anglophone’s list, and there’s no place for Mother Joan of the Angels. It’s a list made for sound, and there’s no place for The Golem: How He Came into the World. I’m not a critic. I’m a guy who subscribes to the Criterion Channel and Mubi, likes to DVR TCM, and loves a good public domain silent film on YouTube or Wikipedia. I bring up these other movies, which are all accessible enough that a guy like me can find them, to wonder why the critics aren’t taking them up. If I can name half a dozen movies off the top of my head, surely people who are in deep with horror can name many, many more. I had this horrible thought about these critics’ lists I can’t shake. If I were a better student of horror movies, would I look at these lists through the same condescending eyerolls that I use to view the AFI Top 100?

The 2024 Horror Canon

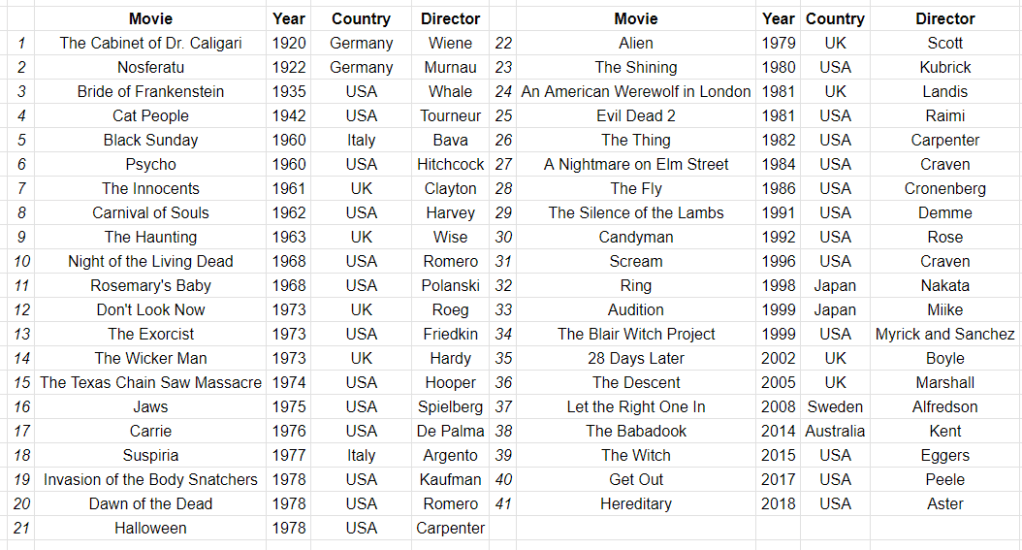

At the risk of using seven critics’ lists and one readers’ list and calling it a canon, here’s a canon. On the basis of the Potter Stewart “I know it when I see it” rule brought up for Jacobellis v. Ohio, you might also look at this and see a canon. It includes all movies that are on seven or more of the lists.

And here are the movies mentioned six times, the near-misses. They are the exceptions that prove the rule.

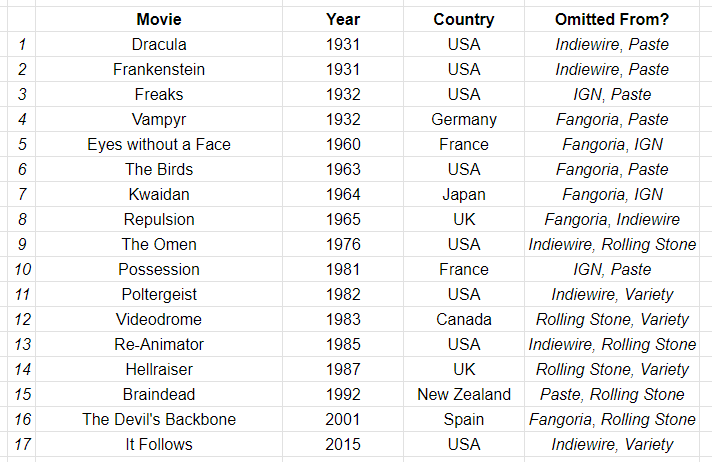

The seventeen six-timers, as is often the case for movies that don’t quite meet the standard of canonization, are probably more interesting as a group than the forty-two listed above them. Arthouse freaks like me are like pigs in poo: Vampyr, Eyes without a Face, Kwaidan, Repulsion, Possession, Videodrome, The Devil’s Backbone. Some of the acknowledged pillars of the horror genre are here, like Frankenstein, The Birds, and The Omen. Popular favorites like Poltergeist and Hellraiser, and true niche gorefests like Re-Animator and Braindead, are hanging around. And who’s to say that in twenty-five years, It Follows couldn’t replace The Babadook or The Witch or even Hereditary on the lists to come? Among this select group you can find breadth of subgenres and decades, but also depth of technique and feeling.

As ever, I can’t actually explain what the listmakers were thinking when they put together lists without these movies, but in some cases I think it’s fairly simple. For a movie that didn’t poll well enough for Fangoria, the answer is almost always that it’s a movie in a language other than English. Paste is probably the most irreverent of the critics’ lists, and classic fare is unsafe with them. Indiewire comes off as more idiosyncratic than irreverent, but the effect is similar in cutting out a number of popular titles. Those two “conspired” to leave Frankenstein out of our makeshift canon, but it makes a certain amount of sense. In 1998, the AFI called Frankenstein the eighty-seventh best American movie; by 2007, they omitted Frankenstein entirely. Bride of Frankenstein, which by my math is one of the fifteen best-received horror movies, is at this point far more fashionable to the smart set than Frankenstein. Thus Indiewire. Paste, for its part, seems to have made a joyous point of leaving Frankenstein off their list. Not only does Bride appear, but Son of Frankenstein and the ’57 Hammer Horror Curse of Frankenstein are there.

Back to our canon. Average year of release 1977, and with the exception of the ’50s (shut out!), at least two movies from every decade from the ’20s to the ’10s. The 1970s are represented with eleven movies, and no other decade has more than seven. These movies come from just seven countries, and this group is seriously Anglophone. A number of past and present luminaries in the genre are represented: Italy’s Dario Argento and Mario Bava, visiting professors like Steven Spielberg and Stanley Kubrick, new voices in Jordan Peele and Ari Aster, real freaks like James Whale and David Cronenberg. And three men, perhaps even the three you’re imagining, each rate two movies and thus make up one-seventh of this list on their own: George A. Romero, John Carpenter, and Wes Craven. Canons are predictable creatures, and this one is no different.

I’ve broken down the canonical movies by how many lists they appear on within the top twenty-five.

By this measure, we can see tiers developing. Alien, The Shining, and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre make Tier 1. Romero and Carpenter each get their movies into Tier 2, joined by Psycho, Rosemary’s Baby, and The Exorcist. Tier 3 starts with Get Out and Jaws and goes through The Blair Witch Project. I think all of these speak for themselves. Tier 4 finishes out the movies which appear on all eight lists, although their placement on those lists is weird. There’s obviously some level of passion for a movie like The Wicker Man or The Descent, but also…is there? The movies of Tier 4 are the movies which show us the pro forma elements of these lists, once half of the lists no longer act like the movie has to be in the top 25.

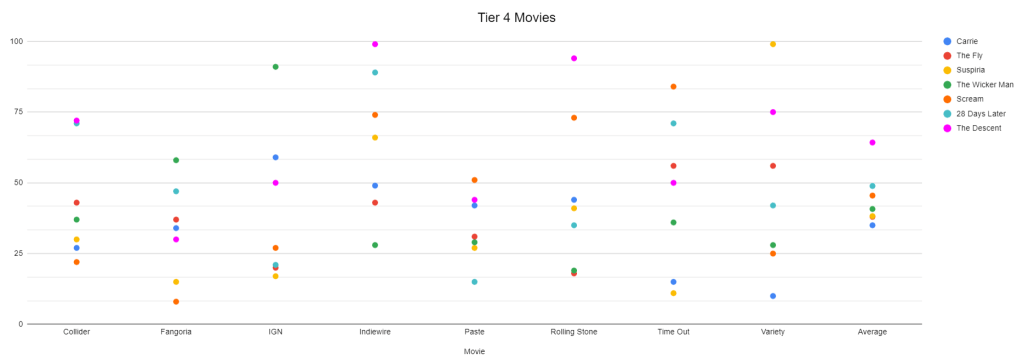

Here we can see where Scream, Suspiria, 28 Days Later, Carrie, The Fly, The Wicker Man, and The Descent rate on each of the eight lists.

I like that it’s easy to see what each list makes of these Tier 4 movies. Paste is high on them, as a general rule, and so are Collider and Fangoria. Indiewire not so much. I also think it’s neat that the averages for these other movies are so tight. Six of these seven movies are, on an average list, within fourteen spots of one another. The Fly averages 38 even. Suspiria averages 38.25. With one exception, there’s a tacit agreement between our lists about what kind of movie deserves to be on each list but deserves to be near the top but rarely. We keep them between the 35th and 50th percentiles. They’re safely, if not riotously, included in these lists.

Then, in its own little world, lies The Descent. Its average score is 64.25. If you told me a few weeks ago that I’d be writing about how The Descent is more entrenched in the horror firmament than Frankenstein, I’d have given you a weird look. As we’ll see on an upcoming chart, The Descent has an average placement only slightly higher than Possession, which isn’t even on two of the lists. Fangoria has it thirtieth, but its highest place on a critics’ list is forty-fourth from Paste. Rolling Stone has it ninety-fourth; Indiewire squeezes it in at ninety-ninth. The Descent has threaded a very, very small needle. There’s a general agreement that this is a great horror movie, and there’s a general agreement that it’s not that great a horror movie. We don’t get that many clues about what pulls it up short from the listicles. Mark Peikert of Indiewire basically just sums up the movie: it’s scary in two ways. IGN and Paste both praise the writing of the characters, which genuinely works in this movie. It’s efficient writing which doesn’t have to linger too long on any one character, and which gives us understanding of each character as she is picked off. The Variety blurb reads like it was written by Clippy on his sixth cup of coffee. Reading through the blurbs, they’re missing passion. When it’s on each list but averages in the back half of the top 100, then you get the sense that the length of these lists outstrips the enthusiasm. The Descent becomes the kind of movie that you inevitably put on a list like this, rather than being the kind of movie that underlines a genre. In a weird way, the numbers don’t lie.

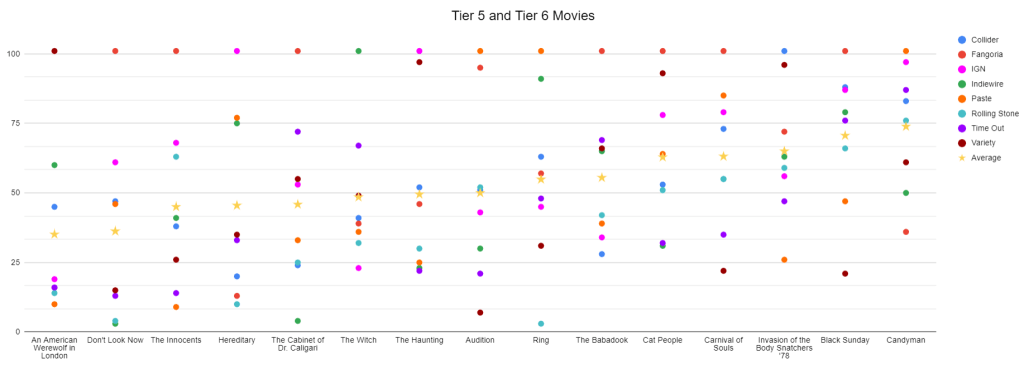

Here’s the same chart, but for every movie which appears on seven lists. If a movie doesn’t appear on a list, I entered a rating of 101. Tier 5 contains six films, all of which have three top twenty-five mentions: An American Werewolf in London, Don’t Look Now, The Innocents, Hereditary, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, and The Haunting. Tier 6 contains all other movies with seven placements.

Here’s where Fangoria is primarily to blame for a slightly smaller canon. Don’t Look Now, The Innocents, and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari do not appear on that list. The critics are also to blame, though. Hereditary, which I thought was a shoo-in for all lists at the outset, couldn’t crack IGN. Nor could The Haunting. Indiewire, ever the provocateurs, kept The Witch from joining Get Out as one of the keystones of elevated horror. Most surprising of all, I think, is that An American Werewolf in London didn’t make it on the Variety best 100. Even Indiewire had it sixtieth. If there is a silver lining for all of these movies, up through Carnival of Souls, it’s that each one has an average score better than that of The Descent. An American Werewolf in London has as many top twenty-five votes as Bride of Frankenstein, Nosferatu, and The Silence of the Lambs. It has more than A Nightmare on Elm Street and The Blair Witch Project. Clearly there was a clamoring for this film in the critical group texts. It’s the most highly rated werewolf movie with a silver bullet. I don’t know what kept it off the Variety list. I’d say it was because John Landis has been justifiably canceled now that we’re putting some blame on him for killing three people during the shooting of the Twilight Zone movie, but Variety includes two movies by Roman Polanski. The simplest answers are probably the best. At least one person at Variety really doesn’t like American Werewolf, or there was some indifference to the movie from a few of the listmakers. I don’t blame them. I think the film is overrated compared to consensus, and furthermore I find the much-lauded soundtrack to be hacky. My own response to American Werewolf is one of the reasons I’m not all that riled up about Suspiria at 99 on the Variety list, A Nightmare on Elm Street at 98 on the Indiewire list, The Last House on the Left at 100 on the Collider list. It really is an honor just to be nominated.

That’s true for Candyman, which has the dubious distinction of having the lowest average score of any movie in the top six tiers. Coming in at 73.875, Candyman is just shy of being a bottom 25% performer. Fangoria has the movie at #36, Indiewire at #50, and Variety at #61. Those are the three scores pulling Candyman up. Every other placement is below the average. Bless the readers of Fangoria for seeing the value in Candyman where other lists treat it in more or less the same way they treated The Descent. Candyman is at least as difficult as the movies of the elevated horror boomlet, even if it came out twenty years too early to qualify for that historical moment.

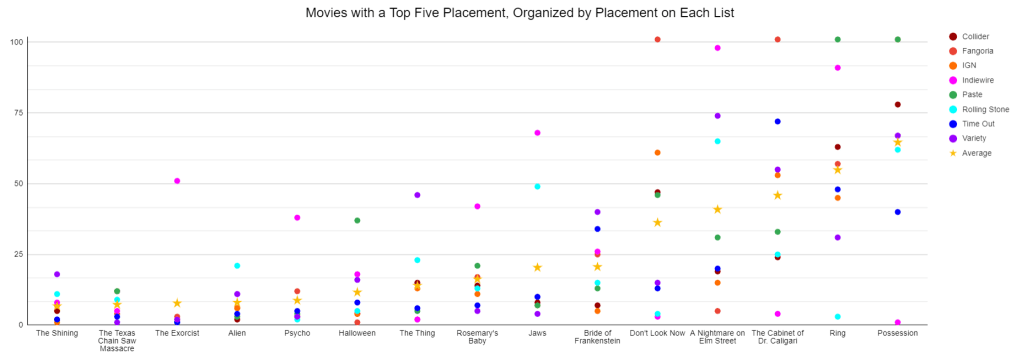

Let’s look at the other side of coin which bears The Descent and Candyman on the face. Here are movies which are cited in the top five of at least one list. Another way to put it is that these are the movies which are most passionately named, even if they don’t make every list. We haven’t talked so much about the movies that have been highly ranked across multiple lists, but here’s our chance.

Here it is, folks. By this measure, The Shining is the lord of all horror movies. It averages a placement of 6.75, where The Texas Chain Saw Massacre averages 7.25. As far as my limited math can tell me, the difference is that The Shining is in the top eleven of every list but one, which is eighteenth on the Variety list. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is ranked twelfth on three separate lists. Next is The Exorcist, which is ranked in the top three of every list but Indiewire. First for Collider, Paste, Rolling Stone, and Time Out. Second for IGN and Variety. Third for Fangoria. The Exorcist is “too tame” for Indiewire, which placed it fifty-first. Love those guys. Indiewire is also the low publication on Psycho, Jaws, and A Nightmare on Elm Street, so The Exorcist is, at the very least, in very famous company. Alien is the third movie that appears in the top twenty-five of each list, bottoming out, as it were, for Rolling Stone at #21. Another way to look at this is through subgenres. The Shining is the most lauded paranormal film. TCM is the most lauded slasher, The Exorcist tops among Satanic horror movies, Alien first among monster movies. I’m tempted to agree with all of these interpretations as who doesn’t live and breathe this genre, but, like we talked about before, I am a little afraid of how little variety there is at the top. If I could make these choices, surely someone else should be able to make more informed and more fitting ones.

The most interesting inclusion here is pretty clearly Possession, which is the only movie to have a top-five placement while appearing on only six lists. More than that, it’s first on the Indiewire list. (Indiewire also singlehandedly got Dr. Caligari on this list.) Possession is a fabulous choice for the greatest horror movie ever made. It’s stylish. It’s terrifying. Isabelle Adjani does things in that movie that I’ve never seen anyone else do, and if I’m lucky I won’t have to see anyone else even try. The creature work is outstanding. The thing is that no one seems to agree with Indiewire, not even a little. The closest we get is Time Out, which spotted it #40, and from that point on no one has it in their top sixty.

One of my running interests is to figure out where that line is between “I may not personally think this is the GOAT, but at the very least I’d hear you out” and “I’m not sure I agree 100% on your policework there, Lou.” If I were putting together a top 100 horror movies list, I can’t promise that Scream would make it. But given its reputation, its influence, and its popularity, I could hear an argument for it as the greatest horror movie ever made. I feel that way about a number of movies in the first four tiers. If I were doing this, I’d probably be basic. I’d be hard-pressed to go against The Texas Chain Saw Massacre or The Exorcist for the top spot. But I’m intrigued by the idea of The Fly or The Wicker Man at first overall. I’m not enthused with 28 Days Later or The Descent the same way, though after having gone through this little journey I’d at least listen to someone who wanted to make the case for those movies.

The Way of the Future

When we look forward a little bit to imagine what might crack the canon in ten or fifteen years, it’s hard to see a potential interloper. The faddish periods of each subgenre have, by and large, been ignored on these critics’ lists. The slasher thrills of the ’70s and ’80s yield only three entries in the canon (Suspiria, Halloween, and A Nightmare on Elm Street), and of those three, only Halloween works as a straitlaced exploration of that genre. The paranormal movies of the late ’00s and early ’10s turned into…nothing, basically. The Conjuring and Paranormal Activity are on four lists apiece. Insidious and Sinister are only represented on Fangoria. Even some of the most talked-up horror movies of recent years got no real traction. Midsommar, which I distinctly remember as the movie no one would shut up about, one of the paragons of elevated horror, shows up as often as Shaun of the Dead and It. Barbarian, which was a little phenomenon of its own, only sneaks in with Fangoria. Saint Maud, which was a trendy pick for the smart set a few years ago, is on two lists. The Purge is nowhere to be found. Ti West got more recognition for The House of the Devil (two placements) than he got for X, Pearl, and Maxxxine combined. The Terrifier franchise is shut out except for Fangoria, which plucked Terrifier 2. As we’ve seen already, these lists aren’t so old that we can’t find a place for either The Substance or I Saw the TV Glow, which is the movie from this decade I most expect to see on lists of this nature by 2030.

The Vanity Fair article I referenced before did that thing about elevated horror. Everyone makes a point of saying “There’s no such thing as elevated horror,” or “This term isn’t actually useful,” or “We’ve gone too far in calling things elevated horror.” What the canon shows us, as it currently stands, is that no matter how often critics decry the idea of elevated horror, they sure seem to like it a lot. The four entries from the 2010s are the Mount Rushmore of elevated horror: Get Out, Hereditary, The Witch, and The Babadook. In defense of critics, I think most of them even mean it when they say things about the problems with elevated horror. But no matter how much they might mean it, it hasn’t changed that elevated horror is the only horror from this decade that they consistently see fit to put in the same air as the big names from decades past. The question I have: When will there be room for something which wears its scares on its sleeves as proudly as it wears its metaphors?