Dir. Marc Webb. Starring Andrew Garfield, Emma Stone, Jamie Foxx

Every movie adaptation of the Batman story has to cope with the Joker in the same way that whenever Poochie’s not on screen, the other characters should be asking, “Where’s Poochie?” “The Night Gwen Stacy Died” doesn’t cast quite as long a shadow as Poochie or the Joker, but you can see the fingerprints of the story on a number of the Spider-Man movie adaptations apart from the literal one here in The Amazing Spider-Man 2.

In Across the Spider-Verse, the Gwen Stacy of that story notes that it goes badly for all the other Gwen Stacies who fall for Spider-Men. The event has been canonized. The Spider-Verse comment shows that it’s become mythologized, a death second only to that of Uncle Ben in the Spider-Man lore. Forget the fairly humble origins of the story itself. The story was designed for Aunt May to be killed, not Gwen, but to kill off Aunt May would be too shattering to the rules of the Spider-Man comics. Aunt May perpetuates Peter’s childhood, and gives him family obligations which would be entirely missing without her. Gwen Stacy had less personality than Mary Jane Watson, which seems to have been the point of the character, a good girl who is uncomplicated and doesn’t roll “tiger” off her tongue. Gwen is a Goldilocks of human sacrifice, important enough to be remembered and mourned, not important enough to break Peter Parker mold outright. Other women had served in the demeaning role of damsels in distress in comic books before, but Gwen Stacy is a fridging pioneer. (Worth reading: Gerry Conway’s response to Gail Simone’s “Women in Refrigerators” list. Not because I’m harboring Freudian delusions, but because of how shocked and disgusted he is by how much more violent comic books were in 1999 than they were when he was writing.)

“The Night Gwen Stacy Died” had its semicentennial last year, and as someone who doesn’t pretend to be a true believer in comics, I won’t act like I know all about how it was commemorated or remembered. For all I know, Spider-Man fans may have virtually no opinion about a book that old, or maybe the average fan looks at #121 and #122 and sees them in the same monumentally important way they’re viewed by historians. What’s more interesting to me is that fifty years after the fact, it’s a useful microcosm for any number of discussions we have about older media. Foremost among them: What if one of your foundational texts is a representative example of a, for lack of a better word, problematic idea in the form? Killing off Gwen Stacy isn’t as horrifying as [gestures broadly at Birth of a Nation and Gone with the Wind], but the basic idea holds. American racism is broadcast to us loud and clear through those two movies, arguably the two most important American epics. Comic book sexism is broadcast to us loud and clear through “The Night Gwen Stacy Died,” which is a cornerstone of Marvel Comics’ most important superhero.

This is a long way of saying that The Amazing Spider-Man 2 decides to confront an essential storyline in comic book media, the rough equivalent of remaking Gone with the Wind while maintaining Scarlett O’Hara as the hero. To do this well would require nuance and even profundity. Unfortunately, The Amazing Spider-Man 2…I mean, shoot, you know this as well as I do, the movie is bad to the point of incompetence.

This movie challenges me in the same way that Star Trek Into Darkness challenged me. (Both movies credit Alex Kurtzman and Roberto Orci as writers. I don’t know why you’d hire those guys to write a movie; do sprinters blow their feet off with shotguns before a race?) It’s just hard to come up with things that work in the movie. The electric eel thing appears to have gotten so much pushback that it was the source of a joke in No Way Home, though the electric eels aren’t the issue. It’s obviously dumb, and so it’s easy to blame that as a cause for the dumbness pervading this movie. The eels are scapegoats for a much bigger problem the movie has, which is that the first of its two villains doesn’t have anything going.

Max Dillon (Foxx) has the potential to be something interesting. Jamie Foxx plays him as the kind of guy who sits in his mom’s basement and posts about how the electric eels ruined The Amazing Spider-Man 2, although he’s too nice to say that The Last Jedi raped his childhood. The infantilization of the character is supposed to work as shorthand for our initial sympathies, setting him up as a real nerd in the spirit of the typical ’60s dork. The confident, dangerous Electro is one Alaskan Polar Bear Heater from being Max’s Buddy Love.

There would be no superhero genre if it weren’t for Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and many of Spider-Man’s classic rogues—Green Goblin, Doc Ock, the Lizard, Jackal, Will o’ the Wisp, even Morbius—are technically gifted men who go bad as a result of scientific mishaps. Electro is updated for the movie to fit more neatly into this genre of villain, now a brilliant engineer who gets on the wrong side of the current and through no fault of his own is tortured by his corporate overlords and attacked by the cops. When his beloved Spider-Man appears to betray him (thanks for nothing, NYPD), Max is radicalized. Being ignored, or worse, picked on throughout his day-to-day gets him down but doesn’t break him. Realizing that the bond he thought he had with his parasocial hero is not authentic but the result of celebrity offhandedness is what snaps him in half. All of this is interesting, but the reason we’re obsessed with the eels is because we know that this setup doesn’t pay itself off. The movie isn’t interested in Max’s reasons for breaking bad, and it’s not interested in why he might continue to act so unlike himself as he gains more electrical power. It is interested in how much space he takes up in the movie’s runtime as he faces off with Peter (Garfield) and Gwen (Stone), and doubtless someone had notes on how much money they could spend on that forgettable scene at the power plant. Was it as much money as they spent on the oil rig scene in Iron Man 3? As much as they spent on the “airport” in Civil War? Surely someone cares. At any rate, if The Amazing Spider-Man 2 really wanted to explore toxic fandom, then we would be talking about a movie which would receive plaudits inferior to Black Panther, although in spirit they would be similar. Black Panther is better received among critics than diehard MCU fans, but critics were nevertheless dying for the opportunity to be impressed by a superhero movie. The Amazing Spider-Man 2, if it had left Electro with some sharp comment about how Spider-Man could have stopped all this by being a little kinder, might have gotten some praise. Yet the movie does not even have imagination enough for that.

What The Amazing Spider-Man 2 is interested in paying off is Gwen Stacy’s death, presaged by the warning that her father (Denis Leary) gave to Peter at the end of the first installment: leave Gwen out of this. Peter doesn’t leave Gwen out of this. In fact he relies on her multiple times to defeat Electro. The best stuff in this movie comes from Emma Stone, although Gwen with Spider-Man is nowhere near as interesting as Gwen with Peter. In the first movie, the two of them mutter at each other so much that I wanted to call an exorcist to get James Dean the heck outta there. In this one, where the two of them start together and break up almost immediately, Stone has more work to do. Gwen and Peter seemed to be joined by a magnet. Both of them have good reasons for giving up the other. Peter knows that the late George Stacy was right. As long as he pursues his vigilantism, he will endanger the people close to him. Gwen knows that Peter is not equipped to be a good boyfriend and a good Spider-Man, and cannot stand being jerked around by him anymore. Both of them choose to ignore their wiser voices, and they wind up making out instead. Frankly, it’s hot. I like the idea of Gwen getting the Oxford scholarship and taking Peter with her as a hanger-on; we call that the full Say Anything. Here we are with superhero movie fandom again, but the possibility of what could be is always, always, always more sophisticated and wonderful than the actual payoff. That’s even true in this case, when the movie is explicitly chasing an essential Spider-Man moment.

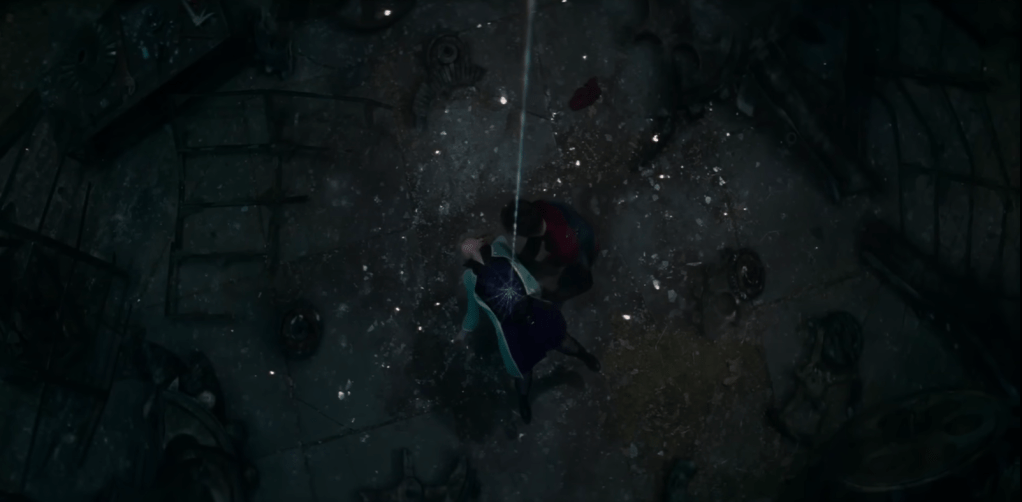

The filmmakers—Webb, Kurtzman, Orci, etc.—have bet the entire movie on Gwen’s dangling corpse. They have bet that Gwen Stacy’s death will leave the same mark on us that it did forty years past. They have bet that Peter’s anguished reaction will crush us. They have bet that Gwen’s death will completely overshadow the entire Electro subplot while making us remember that Gwen did something heroic in her last hour. They have bet that this will lend weight to the psychosis of Harry Osborn (Dane DeHaan), who has been doing the plot of Succession in the back half of this movie. They have bet that we will feel that this moment will be even more devastating than the much-noted death of Uncle Ben. They lose all of these bets, and what it comes down to, I think, is that for this movie, Gwen Stacy is just a woman in a refrigerator. Gwen’s death is not tragic in and of itself, but it is tragic because of the effect it has on Peter. He pops in a flashdrive to watch Gwen’s valedictory, a speech that he missed because he was being Spider-Man, and it’s written to be a transparent message to Peter. It’s a message of hope for the guy who has to pick up being Spider-Man again, not a statement of the value of Gwen’s own life. The value of Gwen Stacy, in this movie, is measured in what Peter will miss out on and not what she will.