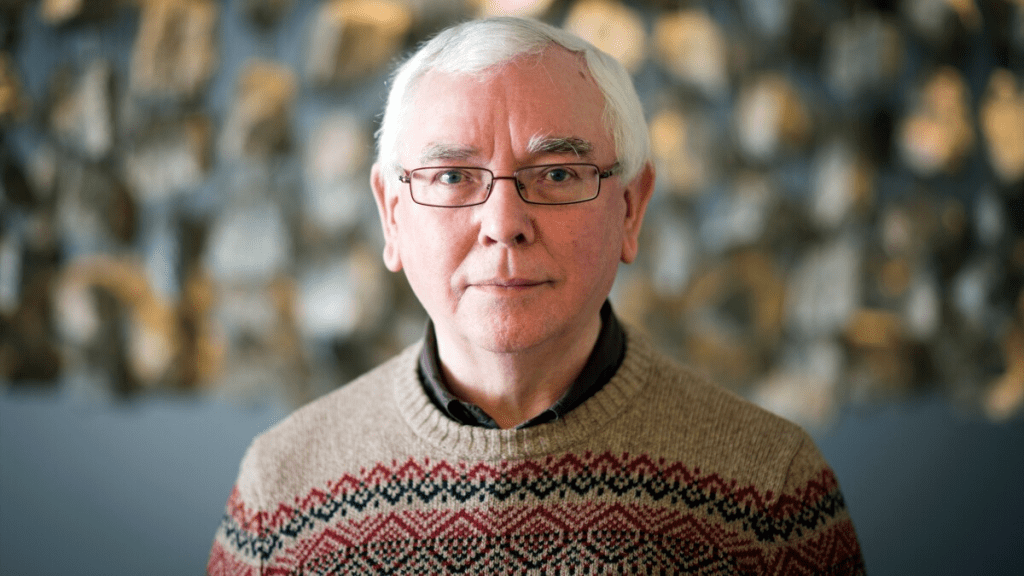

Terence Davies died and it broke my heart. He was a month shy of his seventy-eighth birthday. In the final decade of his filmmaking career, he made four films: The Deep Blue Sea, Sunset Song, A Quiet Passion, and, all too appropriately, Benediction. With apologies to what he had done from the early 1980s and through the late ’00s, when Of Time and the City was released, I think this was the best stretch of his career. The middle two, as middle children often do, succeed on the basis of reserved emotion. There is beauty in those, but no, I would not put either with The House of Mirth or Distant Voices, Still Lives. What makes this the finest stretch of Davies’ career are the vertices; in my opinion, both deserve to be named among the ten greatest films ever made in Britain and Ireland. Davies was still growing when he died, the way that Jean Vigo and F.W. Murnau and Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Andrei Tarkovsky and Krzysztof Kieslowski were growing when they died.

It’s so rare that the last decade of a director’s career can even be considered the greatest of his or her oeuvre in the way that I think Davies’ best movies came last. The director in question must be sixty or older at some point during this great stretch, which sounds very young but also accounts for life expectancy being lower in the past. There have to be enough movies in that period to give us a fair sense of the filmmaker’s quality, too.

On the most obvious level, there are a lot of directors whose earliest forays or mid-career periods are simply their best. Take Davies’ contemporary Mike Leigh, one of the two men (along with David Lean) who might honestly contest Davies for the title of Britain’s most outstanding filmmaker. I think very highly of Another Year and especially Mr. Turner, and I was disappointed that Peterloo made such a small impression. Few of us would take that stretch over the ten year period from Life Is Sweet to Topsy-Turvy, where he made films like Naked and Secrets and Lies along the way. Nope. Two auteurs of the silent era help us see a practical reason why it’s so hard to attain the supremacy of a final stretch. Buster Keaton, maybe the very best of the American auteurs of the ’20s, didn’t direct a picture after 1929. He was betrayed. When he was about the age Terence Davies was when he made A Quiet Passion, Keaton was doing cameos in Beach Party movies. Or take Sergei Eisenstein, who is maybe an extreme example of how a career can be shuttered by one’s time and place. Stalin outlasted Eisenstein, but even if he hadn’t, is it likely that Eisenstein could have walked into the offices of Mosfilm and just restored himself to the glory of the ’20s? And finally, although I’ve compared Davies to men like Murnau, I’ll grant that there’s a difference between dying from cancer in one’s late seventies and dying from a car crash in one’s early forties.

Go through your list of canonical directors and you run into these qualifiers over and over again. There are some aforementioned directors who kicked the bucket too soon for them to be sorted into this other bucket. Kenji Mizoguchi, who was taken by leukemia before he turned sixty, belongs in that group. So does Ernst Lubitsch, who succumbed to a heart attack around the same age that Kieslowski’s heart failed him. Pier Paolo Pasolini was murdered. Chantal Akerman’s best period is probably the earlier part where she made the consensus best film of all time. Alfred Hitchcock and John Ford made their best films in the back halves of their careers, but it’s a lot easier to argue for the enormous wealth of the earlier parts of their careers. Orson Welles doesn’t literally have the Keaton problem but it’s darn close; D.W. Griffith does. Carl Theodor Dreyer and to some extent Terrence Malick didn’t make enough movies to belong in this discussion. Satyajit Ray’s legendary films came earlier than his lesser ones. There’s probably some case to be made for Jean-Luc Godard at his peak in his final years, but I’m sure as heck not gonna make it. Akira Kurosawa is really tempting but not convincing here. Ditto Abbas Kiarostami. Wong Kar-wai has receded from his prolific ’90s, and David Lynch has gone back to Twin Peaks and thus to television. I like Claire Denis’s recent work, but I’m not sure I can put it above that sensational run from Beau travail to White Material. Don’t make us laugh mentioning Steven Spielberg. Everyone agrees that Billy Wilder’s endurance ran out in the 1960s, even if everyone doesn’t agree exactly where. It doesn’t matter how much we reclaim Eyes Wide Shut so long as the very best of Kubrick was there thirty years before. Play this game with your friends the next time you’re driving for an hour or so. It’ll fill the time.

Do we include Yasujiro Ozu here? He was sixty when cancer got him, which is perhaps a little young for this consideration, but his final ten years include the best of his work. If Ozu counts in the way that Davies does, then we might say that he belongs with Davies. Luchino Visconti qualifies in spirit if not in literal time, I think. The Leopard is a little too far back from the actual endpoint of his career to qualify; on the other hand, he did make The Damned, Death in Venice, and Ludwig in his sixties. There is only one other director who I can think of this day who really, truly fits into the same category that Davies does, and more than that, is saving his best for last. That director is Martin Scorsese, who is older now than Davies will ever be, and who seems to be finding new depths within his art the older he gets.

I’ll grant that there are periods of seven years to ten years where Scorsese has made better pairs of pictures than he has from Silence through Killers of the Flower Moon. Taxi Driver and Raging Bull, Goodfellas and The Age of Innocence. Maybe you could argue for The King of Comedy and The Last Temptation of Christ, though I wouldn’t. But I don’t think there is a like period where Scorsese has made three films as good as Silence, The Irishman, and Killers of the Flower Moon. It’s his Judas Trilogy, the stories of men who betray the ones they love and honor. Perhaps The Wager, the film he intends to make next, will be just as good as those films and remove all doubt. Or maybe Scorsese will die before The Wager can even get into production.

One of the thoughts I had as I was grieving for Davies was my belief that there was going to be one more film from him. I knew that he’d been trying to get funding for one, had started working on the early stages of another. Then he died. There was no other Terence Davies movie, despite his best intentions and our dearest hopes. I hope that Scorsese, who in interviews sounds increasingly tired and unsure of his physical capability to work like he did even last decade, will keep making movies. I hope he can make them long enough that a film like The Irishman doesn’t fit into this final decade of his career, and thus makes this musing moot. What’s clear from these past few weeks is that between Davies and Scorsese we have two of the most profound directors to ever do the job, two people who have reached their peaks in their latest years. We may never see that specific kind of greatness ever again.